Artworks

Installations

The title of philjames’s lively and seductive exhibition is Pleasure Island, which he tells me derives from the 1940 Disney film Pinocchio. In the film, ‘Pleasure Island’ features all the things you would expect of a children’s carnival: a Ferris wheel, ice creams and popcorn, but it also caters to darker, more transgressive desires. There is gambling and boozing, a tent for fist-fighting, a ‘tobacco row’ featuring towering statues of Native Americans flinging cigars to hordes of children, and an opulent mansion purpose-built for trespass, theft, and destruction. Along with another disobedient boy, Lampwick, Pinocchio is lured to Pleasure Island with the promise of uninhibited vice. Finding themselves in the demolished mansion, Lampwick looks around for a surface to light-up on and settles on Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, which has been knocked off the wall, out of its gilt frame, and unceremoniously graffitied with a stick figure. “Being bad’s a lot of fun, aint it”! Lampwick declares as he defaces the masterpiece in one broad sweep of match to cigar. The Mona Lisa, a symbol of the highest cultural achievements of Western civilisation, continues to be a target for vandals. A couple of months ago a disguised climate protester smeared cake across it. Mona Lisa’s mutilation is always an act of desacralisation, and in Pinocchio, it is also a violent transgression of the middle-class values that the film sought to instil.

Anyone familiar with philjames’s work knows that defacing art is a habit he enthusiastically pursues. Meticulously adding familiar characters such as Sponge Bob and Bugs Bunny from popular animations to readymade prints and paintings, he treats masterpieces, religious iconography, and kitsch with equal disrespect. This isn’t to say that no respect is paid to the originals. On the contrary, philjames lovingly maintains the dilapidated originals that are often rescued from charity shops and skips. Because his cartoon additions are simultaneously jarring and complementary, they begin an open-ended dialogue between the artists and their subjects that crosses the divide of time and purpose.

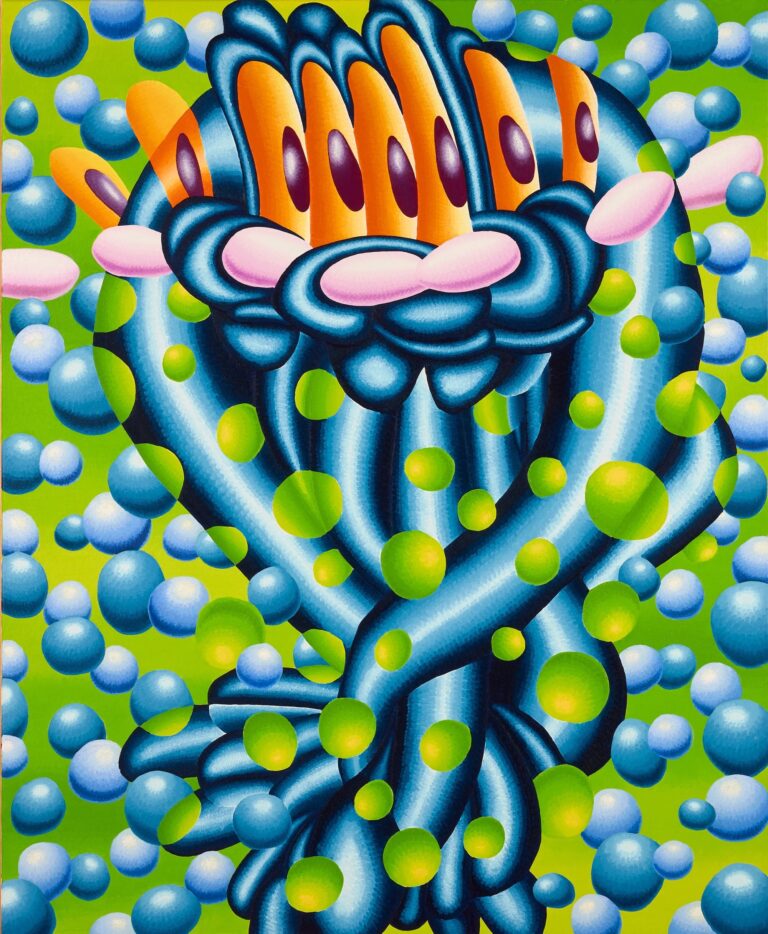

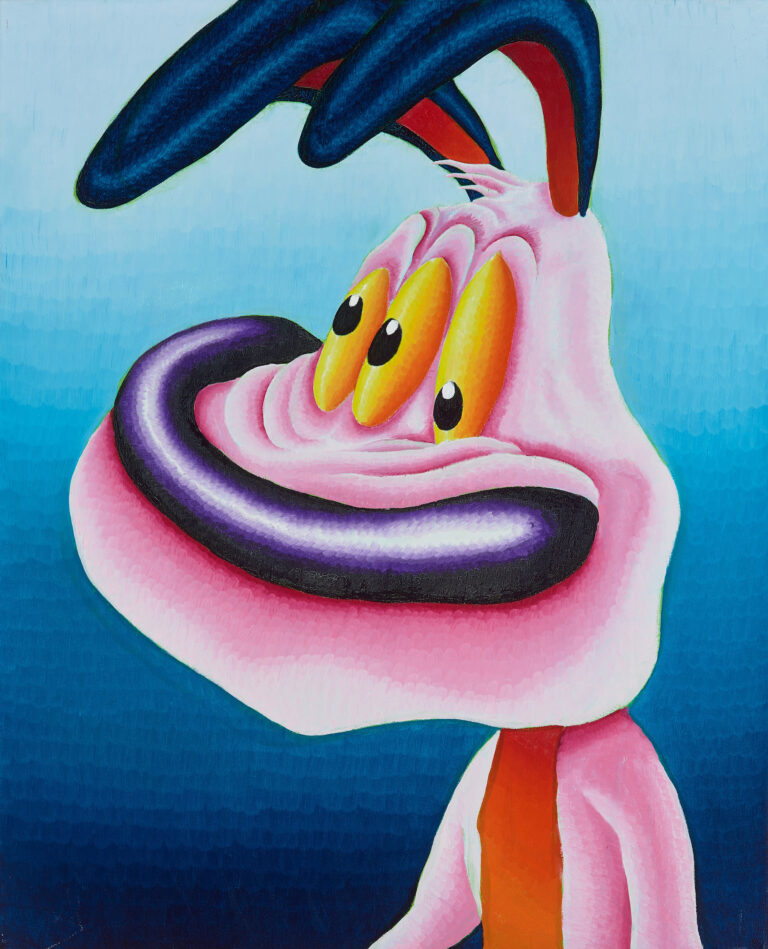

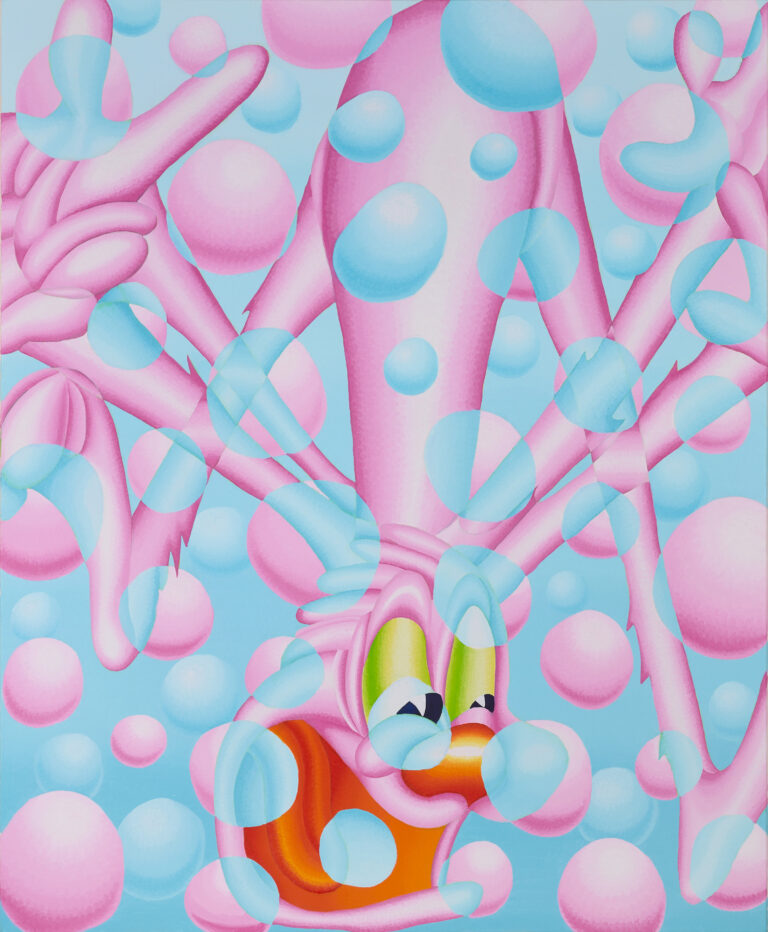

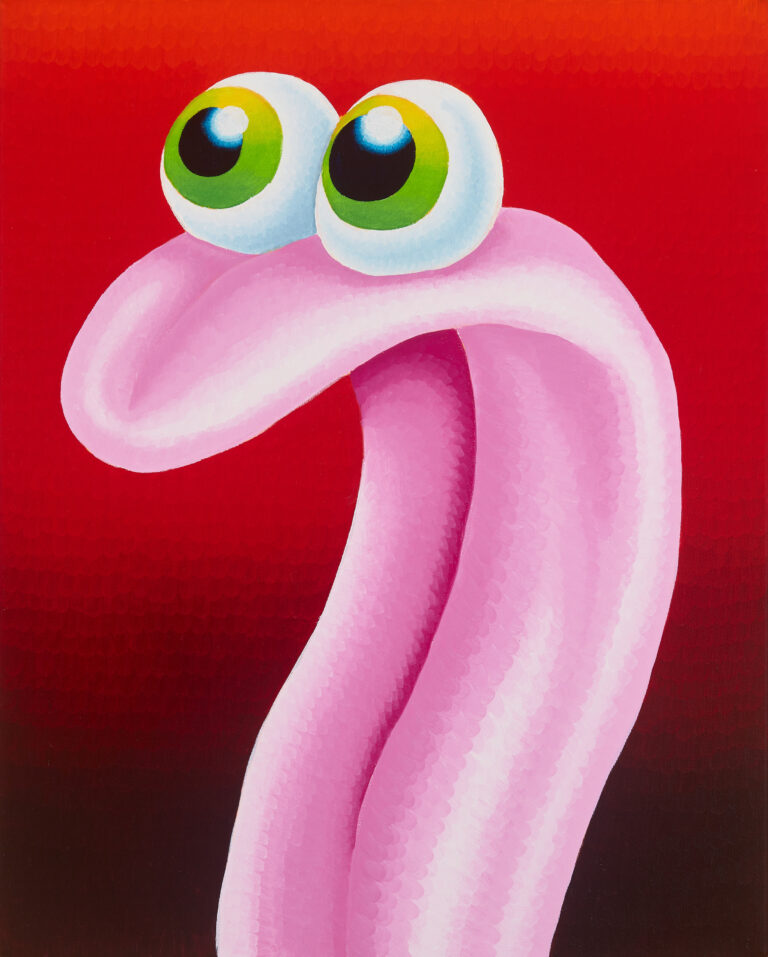

The Pleasure Island series represents a change in direction for philjames. He abandons working directly onto readymades but continues to appropriate recognisable cartoon characters (such as the hand-stitched Pink Panther sculptures) or recognisably cartoonish figures and motifs. By ‘cartoonish’, I mean they have no basis in reality (either in film or television) because they are figments of philjames’s imagination. However, their crude and cutesy traits, and archive of violent and frenzied gestures are so well-trodden in the genre that we instantly understand their language. In this sense most of the quirky inhabitants of Pleasure Island exist as simulacrum: free-floating signifiers without an original. Philjames’s defacements of the past and simulacral displacements of the present are both forms of appropriation that contest language in the form it was received, whether from high art or pop culture. However, while one specifically targets Western art history, the other asks whether animation might more broadly function as a culturally acceptable space for the free play of transgressive instincts and desires.

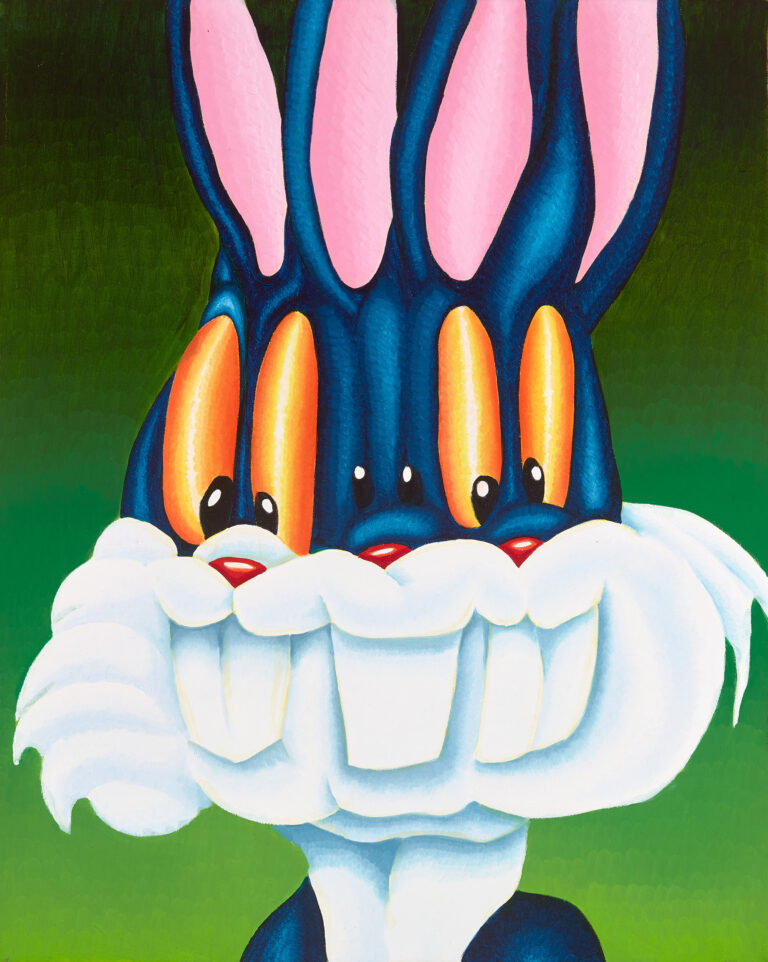

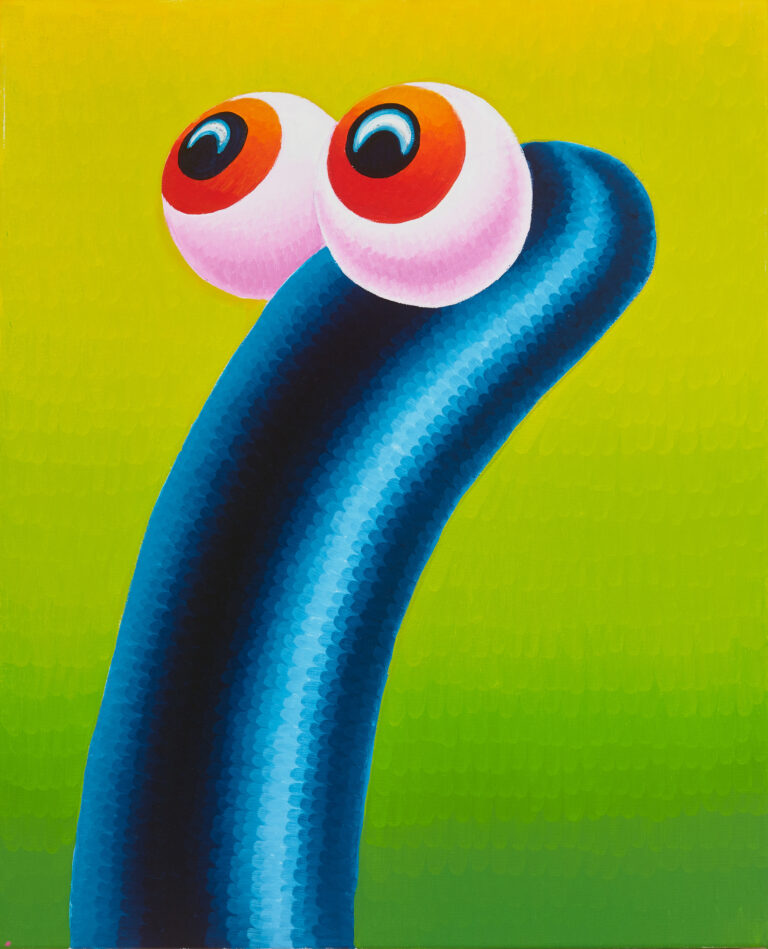

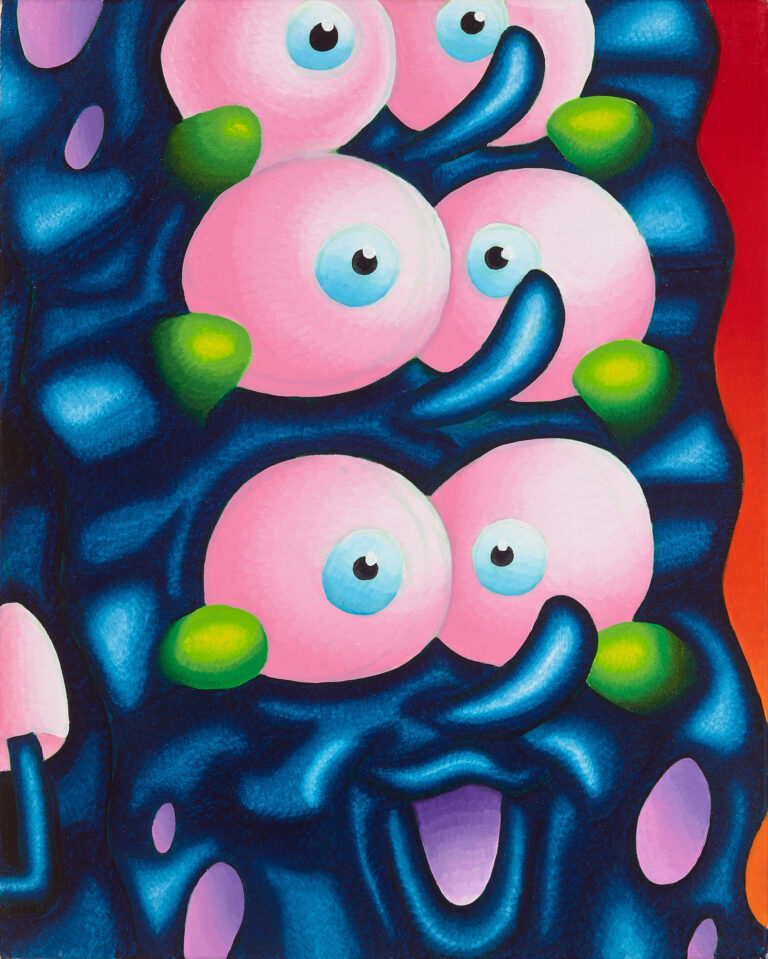

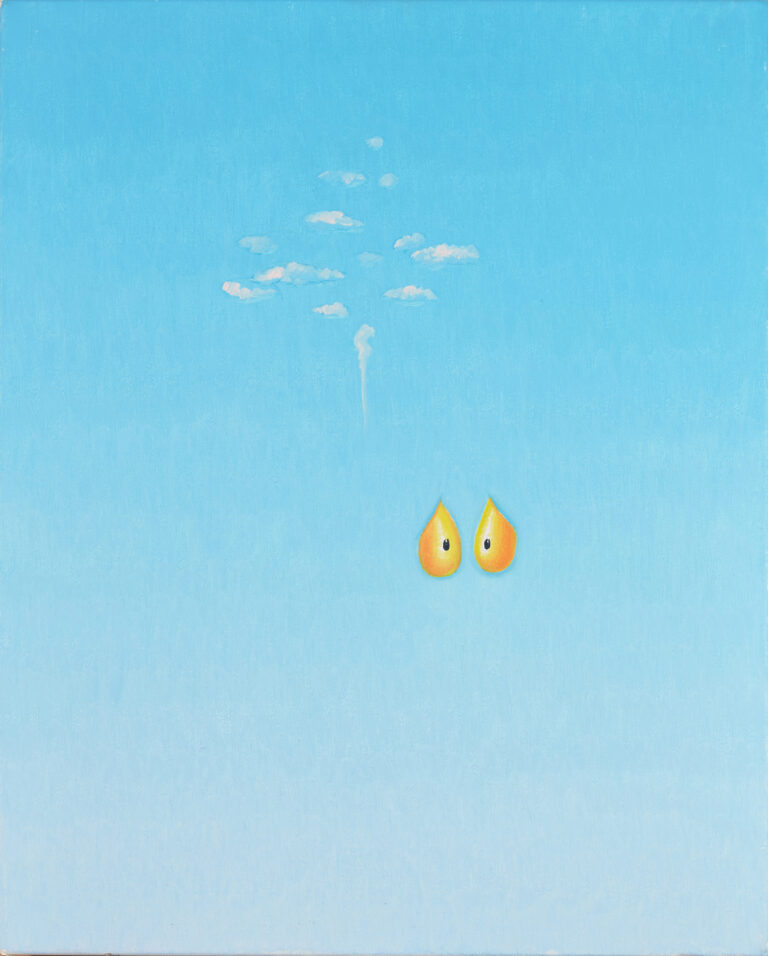

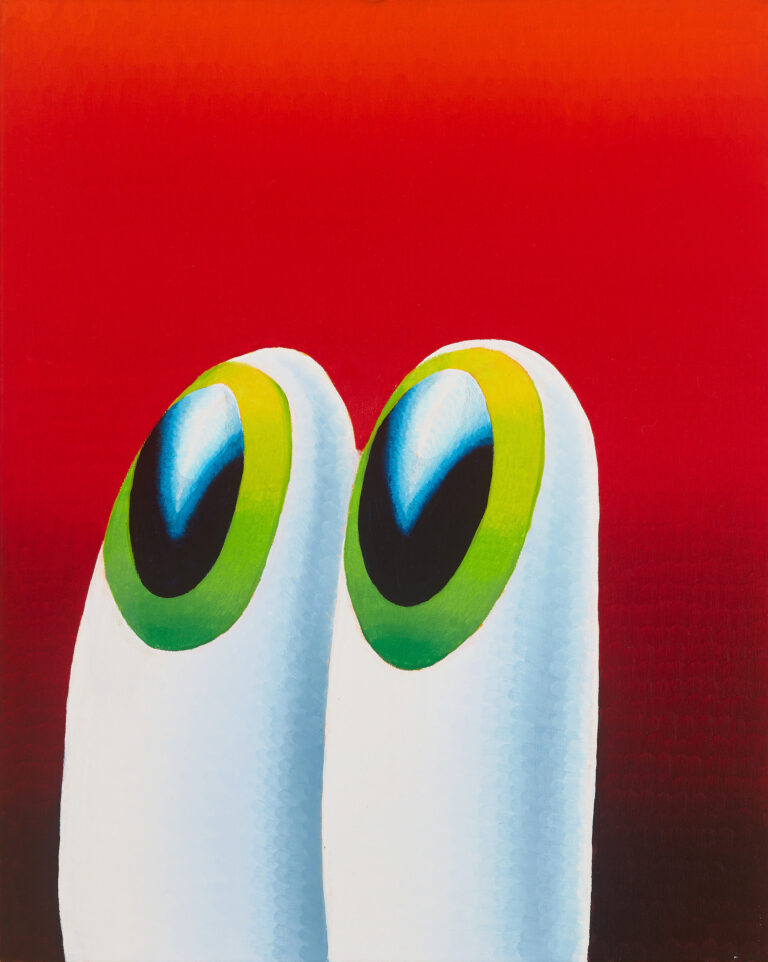

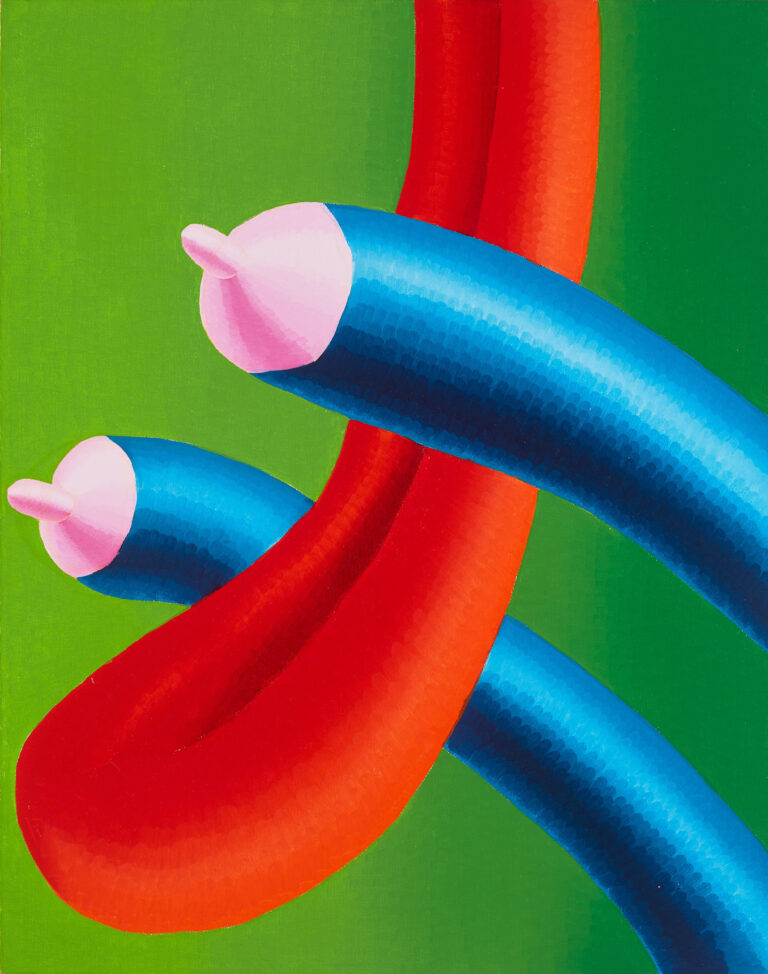

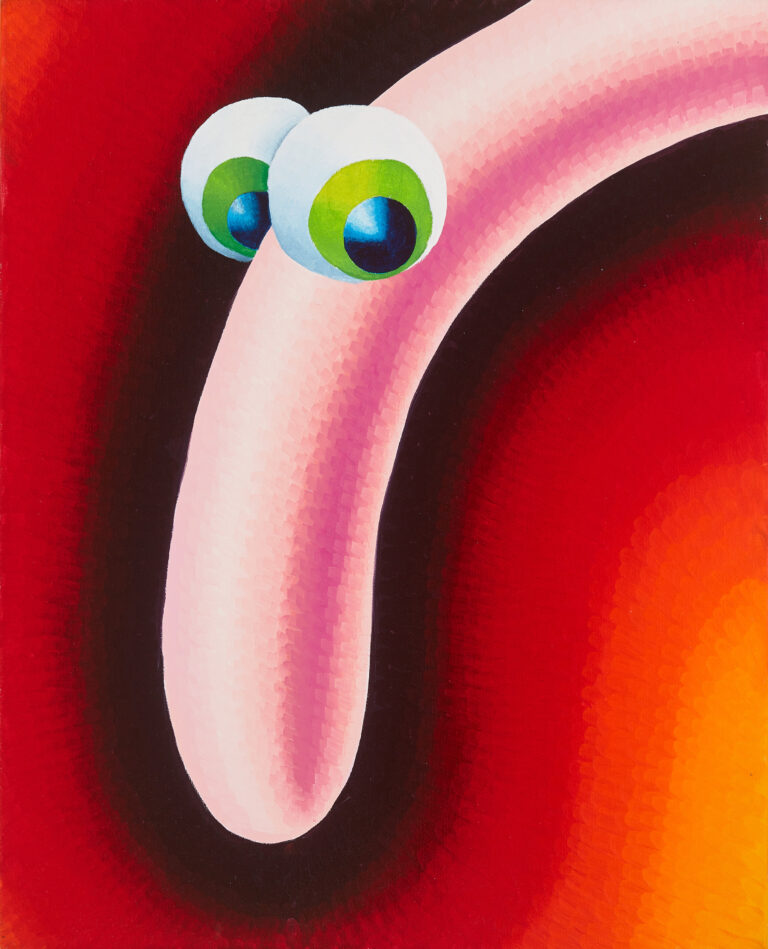

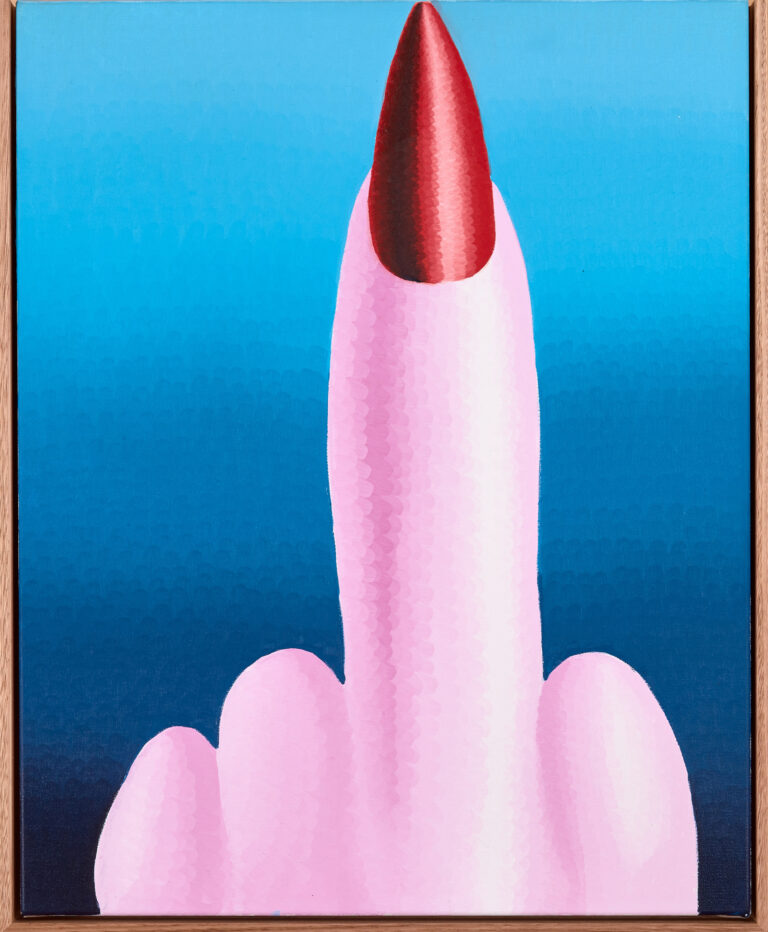

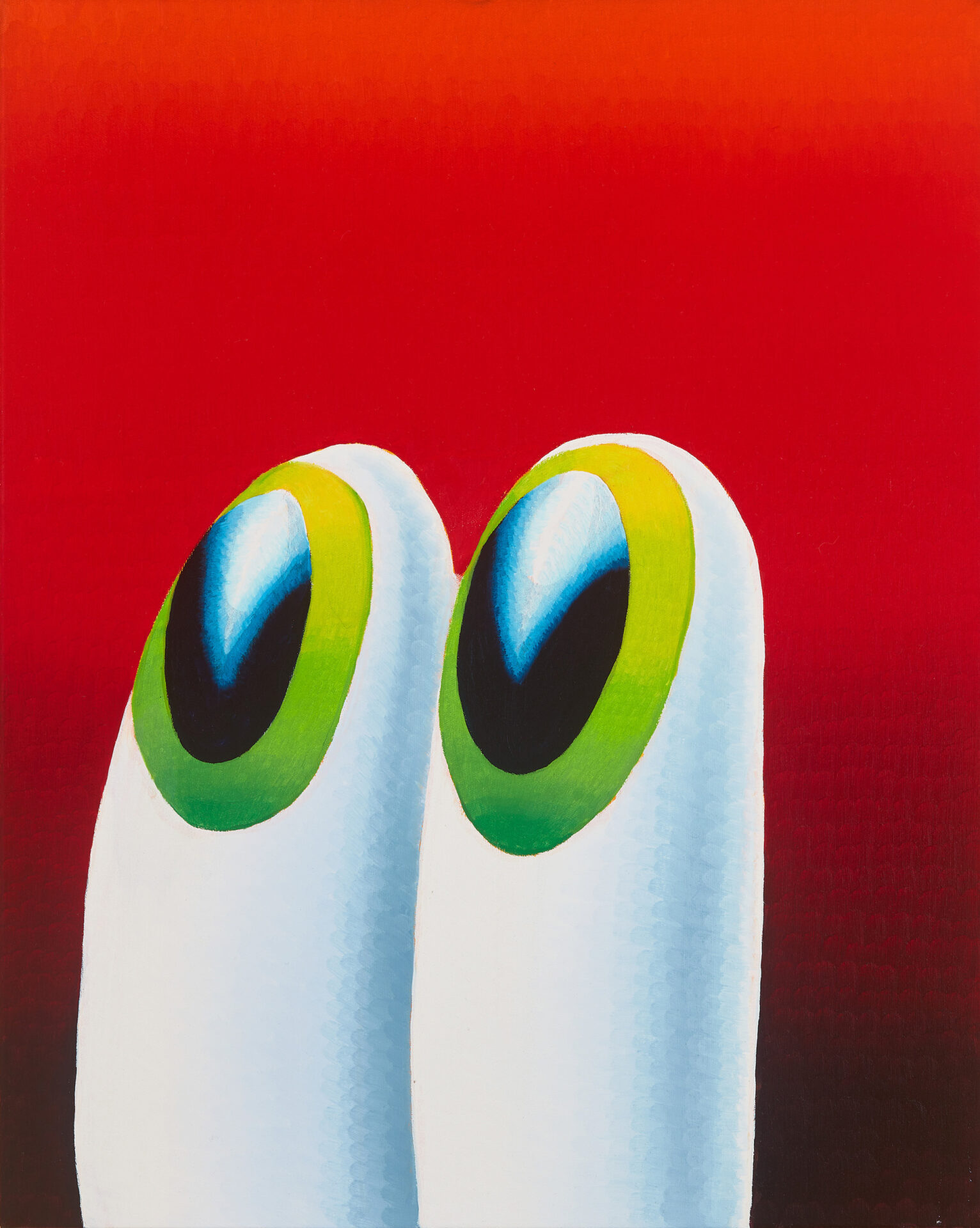

Pleasure Island buzzes with rambunctious energy. Hyperactive ‘toons jostle for attention amongst pneumatic, glistening tits and dicks. The eye never settles, continually drifting from one object of desire to the next. Like a kid in a candy store presented with too much choice and too little time, the spectator is overwhelmed with feelings of urgency and impulsiveness. Dribbling is inevitable. Yet satisfaction is elusive, its promise forever drifting like a carrot on a string at the far reaches of peripheral vision. The paintings of Pleasure Island are generally of two types: monumental animation smears or intimate corporeal vignettes. An ‘animation smear’ is a single frame used between traditional animation keyframes to create the illusion of motion blur. In contrast to real smears crafted for the small screen, philjames’s imaginary ones are epic in scale. In ‘Pleasure #3’ (2022), for example, a bunny suspended on an acid ground explodes into a series of disembodied eyes and limbs that trace an arc of slapstick poses and expressions. The bunny clutches its fists in defiance, jumps out of its skin in surprise, and drops its shoulders in cheerful anticipation all at the same time. Despite their flat, graphic, and reproducible appearance, philjames paints slowly and methodically in oils, layering the surface that takes days to dry. He takes great pleasure in this process, but also in its implications: collapsing distinctions between cultural forms (art and pop) and audiences (adults and children).

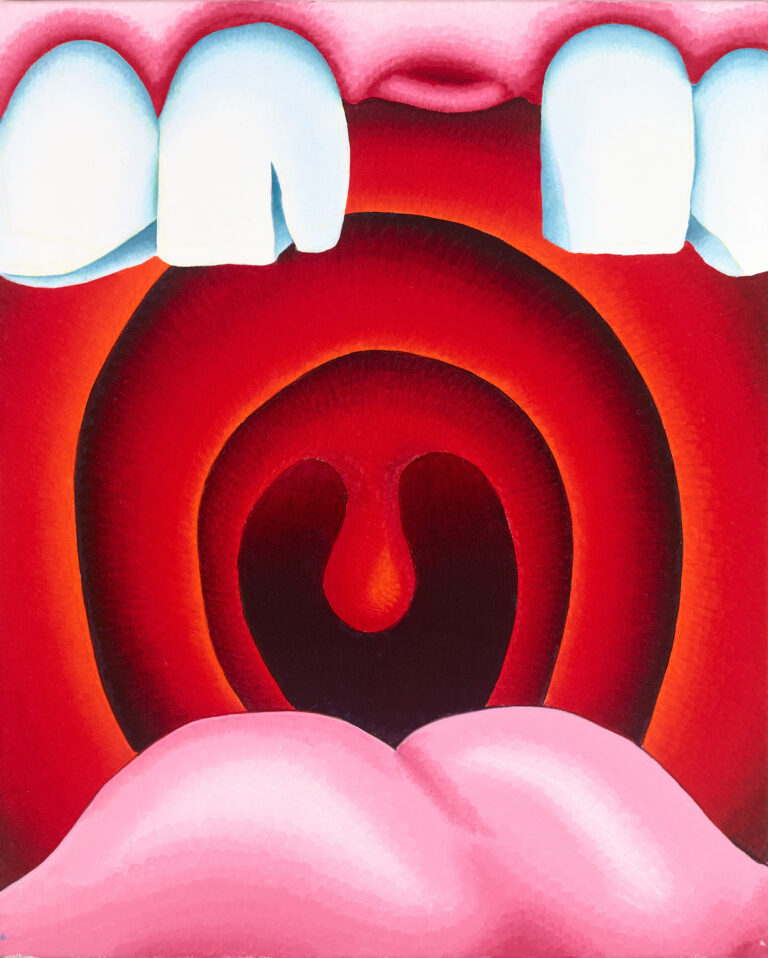

The smaller vignettes are a kaleidoscopic assortment of translucent, inflated, toy-like objects, and although they only allude to body parts, their intimate scale suggests an anatomical crop or close-up. Similar to Man Ray’s erotic photographs of decontextualised body parts, these paintings function like Freudian slips, fetish objects, or unconscious projections. Many feature scenes of seduction and object coupling – from light caresses to more determined instances of frottage. A gaping mouth with chipped and missing teeth, ejaculated goop, and distended tongues that allude to sucking, licking, and biting elicit visceral responses. Like a public erection or a nip slip many of these scenes have the power to evoke repressed shame or failure and can be difficult to confront head-on at first. Nonetheless, in its joyous and unwavering celebration of transgressive desire, ‘Pleasure Island’ provides a safe space for its liberation. It couldn’t be more different to Pinocchio’s version. In the Disney film, essentially an ‘assimilationist fable’, the boys lured by working-class forms of hedonism are eventually turned into donkeys; literally, their pursuit of pleasure transforms them into beasts of burden. The threat of Pinocchio’s Pleasure Island teaches American boys to become productive members of the capitalist patriarchy. Philjames’s Pleasure Island teaches us the value of transgression, the most pleasurable form of which is art.

Jaime Tsai, 2022