Mathew McWilliams has a diverse practice that ranges from rubbings to photographs. He often uses the mark making and techniques of orthodox conceptualism (from the 60s and 70s) but, in a contemporary way, and reinvests the conceptual approach with a real interest in beauty and aesthetic outcomes (including poetic possibilities and slippages, chance and painterly allusions). His work is conceptual art plus.

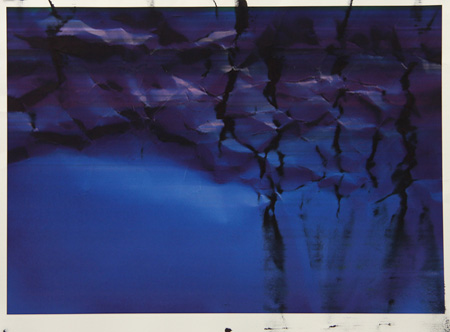

For example this show if it was put into conceptual terms would be about the self-reflexivity of photographic process. It would talk about a conceptual recipe that should be repeatable in a global way anywhere: 1. Fold or scrunch paper; 2. Take a photo of that paper; 3. Print the photo back onto the original (now folded or scrunched paper). The work would amount to a conceptual feedback loop where the photograph quite dryly, merely references itself and nothing much in the world. The 70s were replete with such painting machines and mechanical drawing. The master of that form was Sol le Witt who some say invented, quite consciously, phone in art; he set up an art algorithm and then got associates to complete the work in various galleries around the world. The buyer bought a contract for the algorithm. It is not a surprise that McWilliams will be showing in a curated show at Pallazzo Cesi in the Umbrian town of Acqua Sparta alongside Sol le Witt works later in 2016.

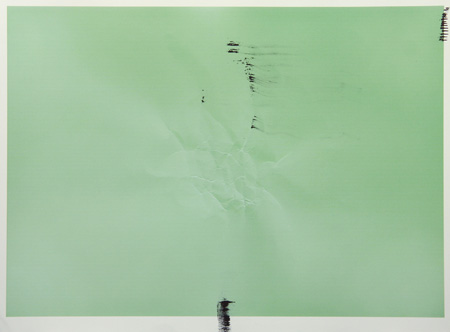

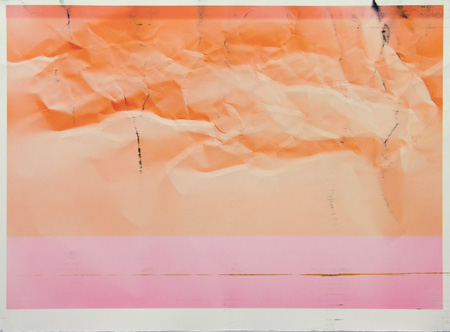

In the end the McWilliams’ works are incredibly beautiful (like Sol le Witt), as if a bureaucrat was found with poetry in their top draw, or indeed drawings coming off the printer. Although he has experimented before with this gambit this series is also tinted and is his most painterly yet. McWilliams suggests that many of the colours and the repeated horizontal forms are reminiscent of one of his personal loves: Rajasthani miniature painting. I can see that but I also see the gamut of western painting from the dusty pinks of Renaissance fresco to the zips of Barnett Newman with many Romantic and Impressionist landscapes in between.

The work is printed on a huge drum printer, an original 80s art printer, the sort that the neologism giclee print was invented for (because inkjet just sounded too technological and machinic). In this printer’s hands ink smudges (over McWilliams’ folds) and the registration often slips. It is this painterly gesture, a machine with a sense of chance, that truly earns it the name, giclee. The title of the show is even more Romantic. The recent storms that Sydney was rocked with, those January and February storms that remind you that Sydney is a Pacific island capital, moved the printer, now artist seismograph, with ground tremors that registered on the works as more inky marks.

But it is for me the relationship to time that makes this work really contemporary. In a small way we can see it in the desperate attempt of the giclee printer to sound French and old, like a lithograph, rather than global and anywhere now, like an inkjet printer. McWilliams work is a study of temporal compression. It speaks to the future, and to utopian abstractions, but it also looks the world like the first ink on soft vellum. The framed paper is at once calligraphy, but also photography (which it is) but also a return to painting. If as Boris Groys says “con-temporary” art is a being with time, rather than being in time, this work absolutely describes that state. McWilliams floats above time and artistic styles and puts a large sheet of paper over all of it, like a net, capturing as much as he can.

Oliver Watts