Artworks

Installations

Oliver Watts grew up not on the leafy North Shore but the watery North Shore, the harbourside suburbs that look out onto the moorings, ferries, pontoons and marine environments of Sydney, a city that is best seen from the water. He is not just from this place but of it: a long-time sailor, the boat shoes appearing in these works must be marked “model’s own”. In the Anglosphere, naval tradition once rivalled the monarchy as a secular sacrament, and Ollie is inheritor to what remains of its near-forgotten rites. His own boat flies the Red Ensign on its stern flagstaff, designating it as a pleasure craft under the Shipping Registration Act of 1981. He once proposed custom-making a chronometer box and then presenting it to Frederik, Crown Prince of Denmark. In his previous practice, he has produced scrimshaw by substituting white perspex for whale ivory. No-one could accuse him of being a landlubber.

But he also, I think, captures an essential waterlogged absurdity in these works, something celebratory and ironic at the same time. There are subtle and tedious distinctions between marine, maritime and seascape art (though all are out-of-fashion) and this show is probably maritime art, the most démodé of all. This means (I think) that it depicts seafaring, rather than mere seacraft or seascapes. It is a genre of painting so synonymous with coloniality that is almost irredeemable: it originated to accommodate the display of British and Dutch warships that subordinated most of the globe. These glowing and rampant depictions of frigates were already making viewers uneasy more than a century ago, and when boats do appear in Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, as in the work of Monet, Manet and Munch, they are often incidental or horizon-bound, part of a landscape, rather than harbour-framed and on a war-footing.

By then, the jingoism that had help buoy British romanticism could only be conjured up artificially or by Americans, and boats in modern painting appeared as bourgeois accoutrements, to be messed around in or with, or as the piscatorial equivalent of something pastoral. Watts works with a volatile compound of these two traditions, but does it with wit. Their whiteness, their masculinity, their class positioning and sentimentality must not only be subverted and problematised, it must also, in his case, be confessed to. It can also be salvaged for beauty, once it has been scuttled.

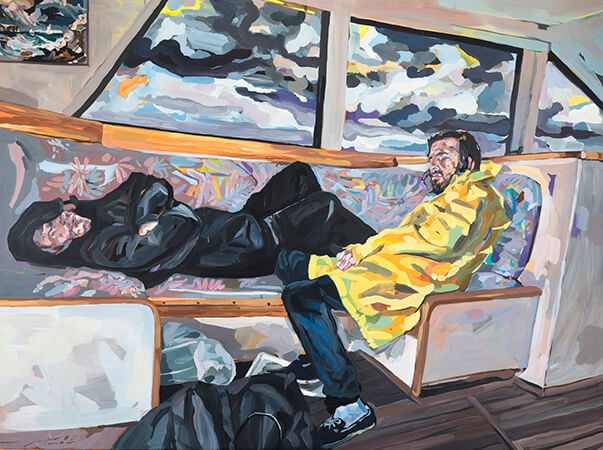

So here the tattered cultural yield of the Commonwealth’s seas – the customs of the people I have heard colloquially referred to as “yacht cunts” – are on display. The boats in these works might be trawling Sydney Harbour, or just outside its heads, in the middle of informal regattas, explorations to chart new swimming holes, or amidst unsuccessful fishing missions (party boats are mercifully absent). I make a cameo in one of the fishing paintings, as one of the fishermen in Seasick Fisherman at Brown Mountains – grey-faced, huddling in a K-Mart anorak, lain next to a similarly under-the-weather Watts (in the corner of the work is a view of Sydney Harbour by Conrad Martens). We were in the hold of yawing tuna boat, and had spent luckless hours trawling skirted lures through chop far off the Heads. Most of the time was spent vomiting, and on return to port asked the wisened captain when he had last caught a fish. Six weeks ago.

In the paintings Ollie is wearing boat shoes (he really did wear boat-shoes); elsewhere his subjects at barefoot. Ben Storrier crosses the Harbour in a luminous sun hat making him look apostolic, dressed in a crossing-the-line outfit that subverts his role at the tiller. This less rugged approach caught a big squid at Sow and Pigs. Eryn Jean Norvill (who herself knows something of retrograde masculine traditions) stands next to a wreck of a sculpture at the Royal Prince Edward Yacht Club in Point Piper. She must be looking out to sea, upstaging an aluminium shape that speaks awkwardly of sails, walrus teeth and money.

Self-portrait in a boat is not such a common picture title or subject as you might think – Google shows only a work by Karl Pavlovich Briullov, aka “The Great Karl”, and its full title – Self-Portrait with Baroness Yekaterina Meller-Zakomelskaya and Her Daughter in a Boat gives something of simpering, pre-revolutionary flavour. It is even rarer to see self-portraits where the painter is all at sea rather than up a river, and Watts’s works carry a secret unease. Self Portrait as Prince Philip Painting on the yacht Britannia has more of that satirical pomp, but its storm clouds also made me think of the Prince’s uncle, bombed by the IRA off Sligo, while aboard his fishing vessel the Shadow V. So too the titular work, Autopilot Steering a kind of joke about who is in charge. But Watts does not look nonchalant reading his books. He looks like a return to some of the oldest imagery we have of the oceans, a man at the mercy of waves.

Richard Cooke, 2019