Artworks

Installations

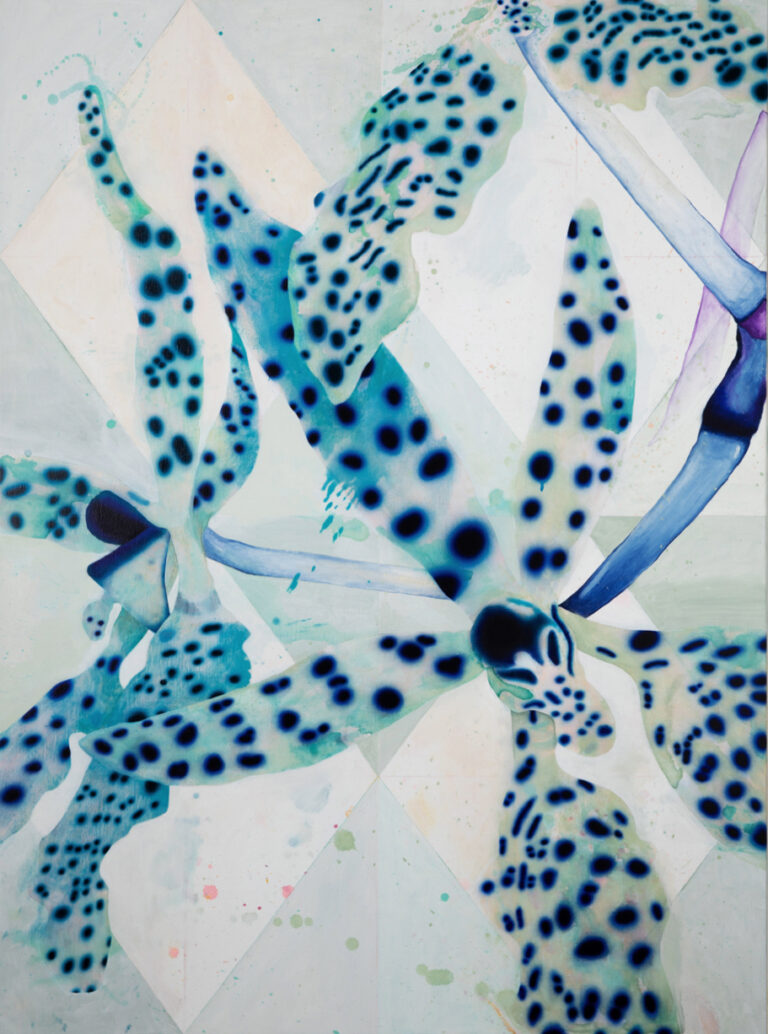

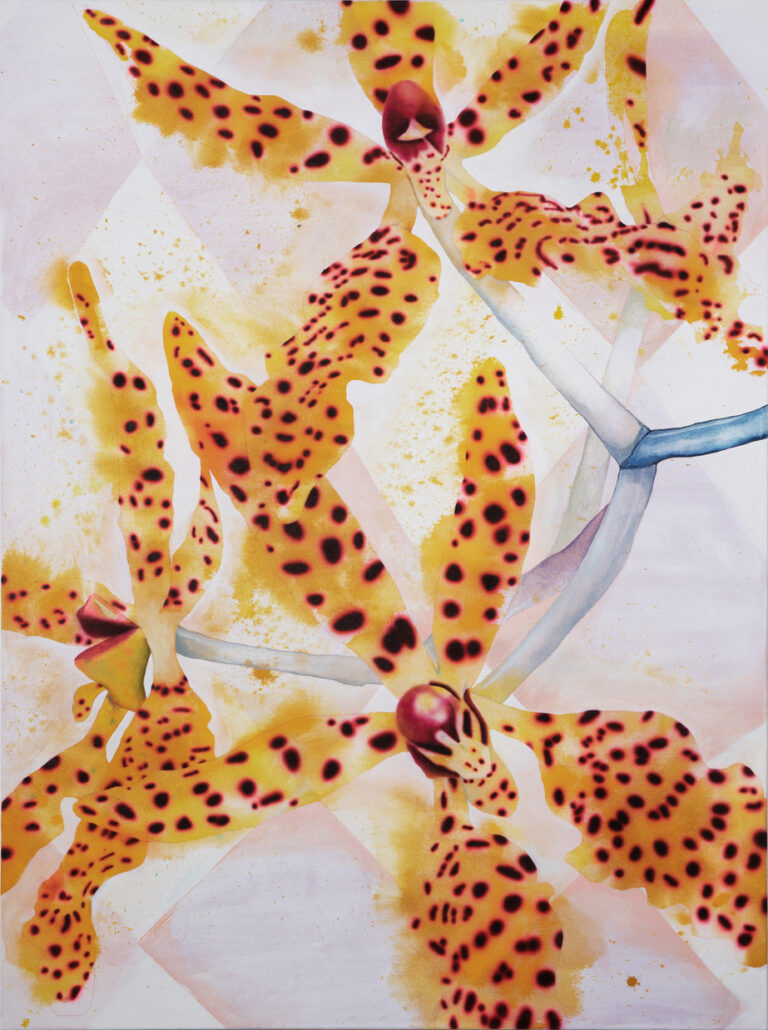

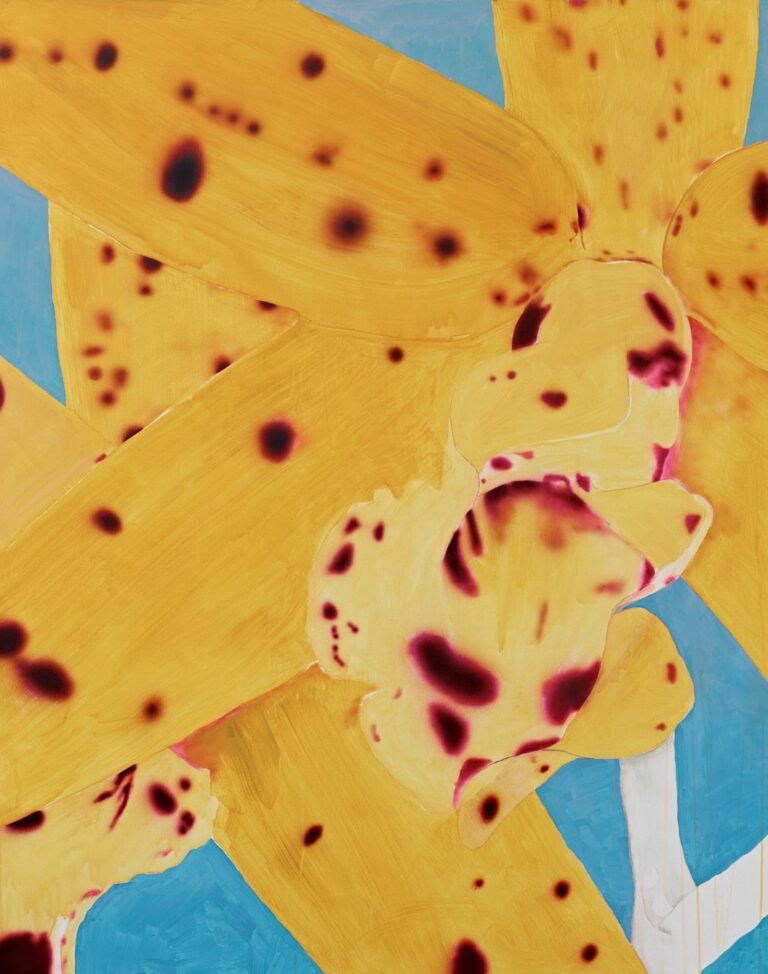

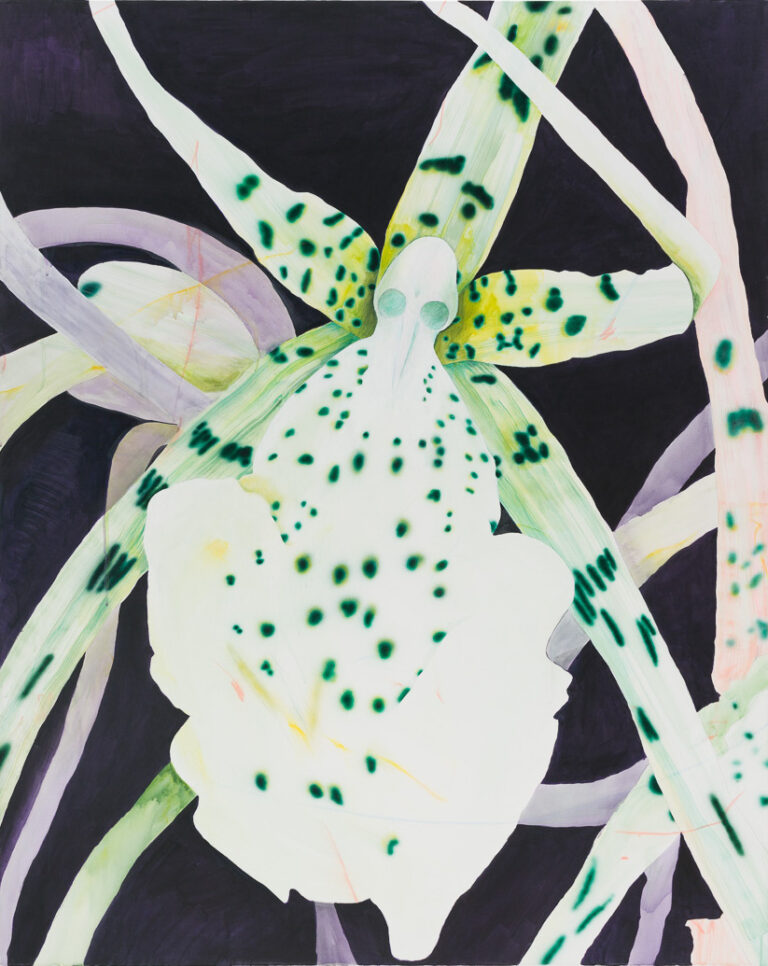

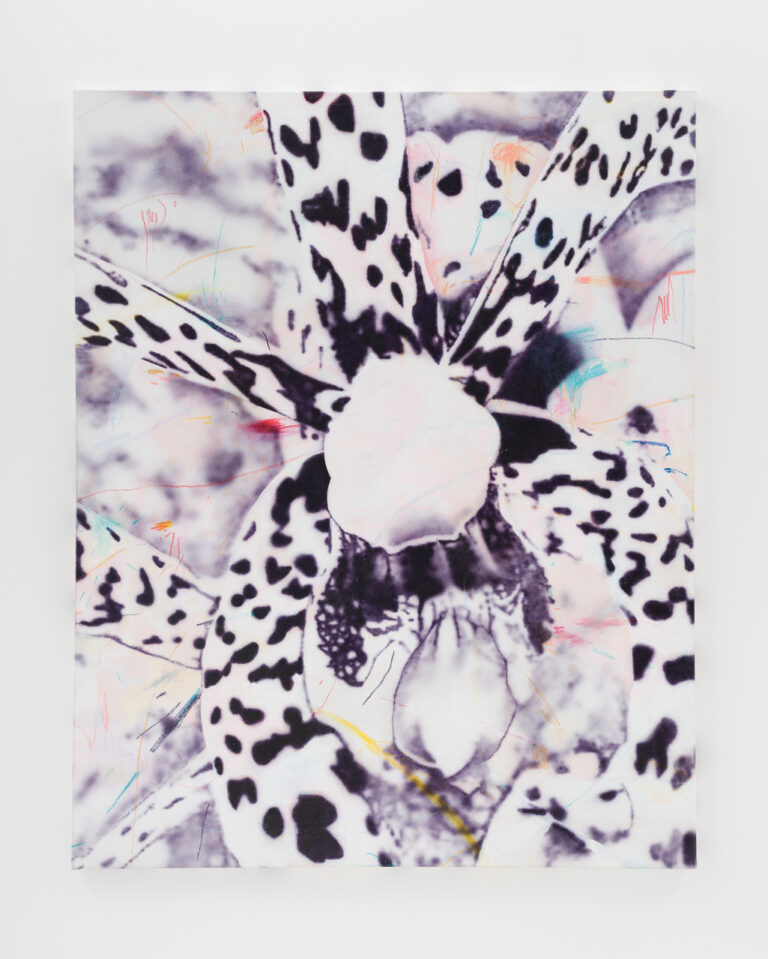

Ben dos Remedios, in his first show for Chalk Horse Gallery, has provided an extended meditation on the orchid. In the (unplanned) context of the Lockdown ending and as flowers bloom in the streets, the show seems to match the genres of old poems and paintings made to celebrate the arrival of Spring: from Chaucer and Botticelli to Eliot’s The Waste Land and Marc Jacob’s Daisy Love, Spring. The gallery becomes an orchid house of (imaginary) scent and dewy air.

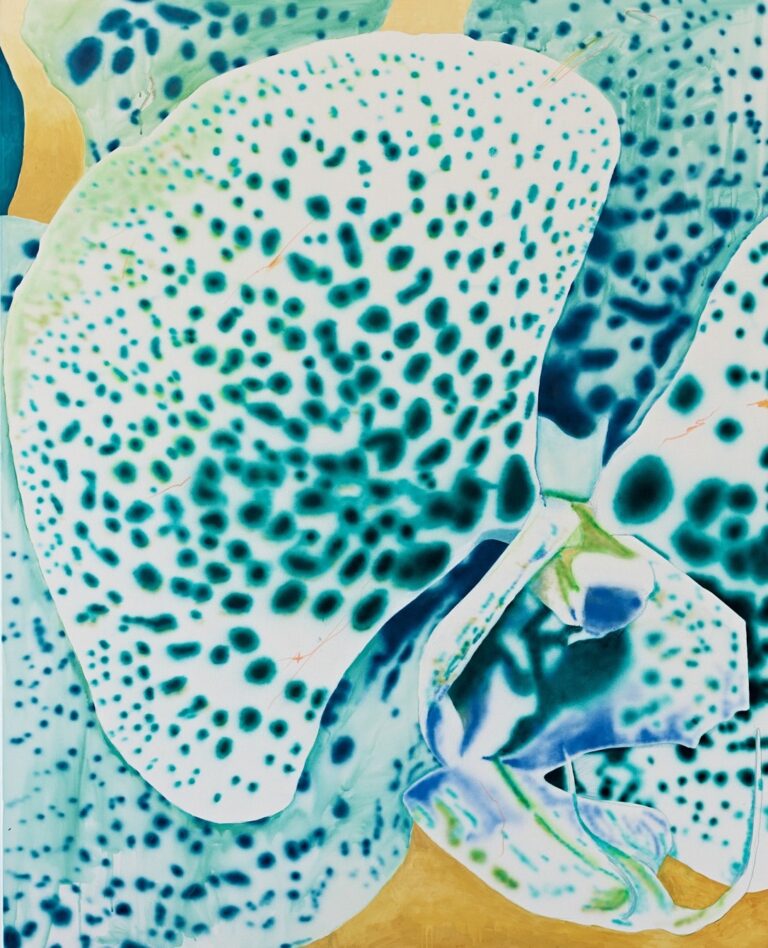

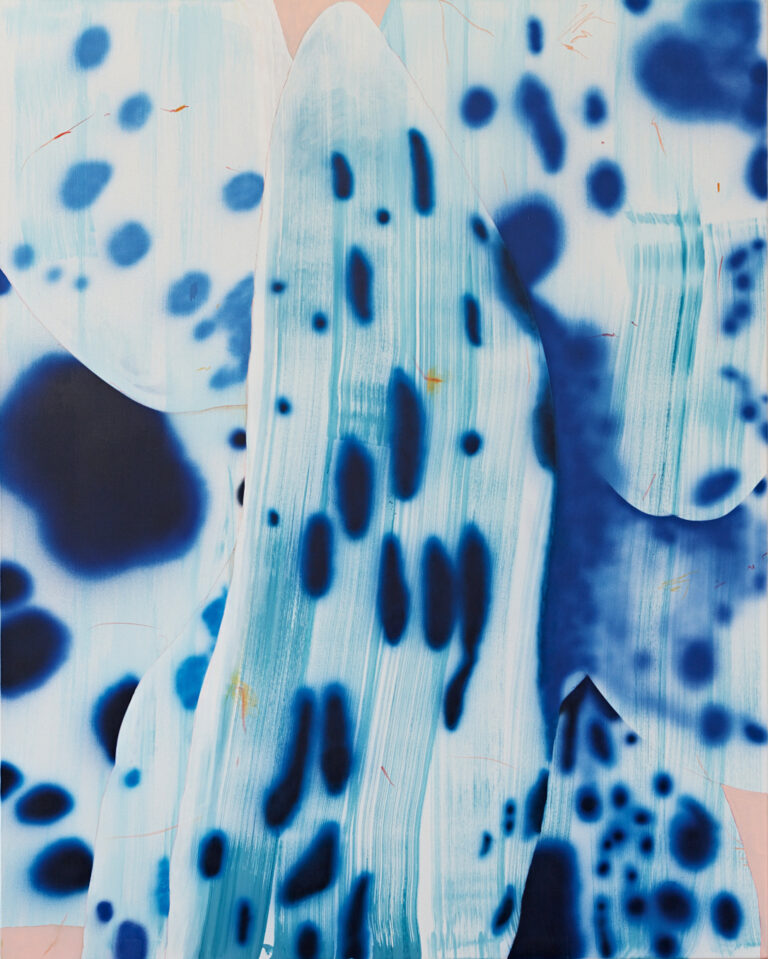

These are not just images of hot house flowers though, fragile and vulnerable, although of course that aspect must still be there. The images that dos Remedios has created, larger than life, sometimes in extreme close up, like a diminutive movie star, make giants of these beautiful and exotic icons of the floral world. The power that they of course wield is a form of seduction, which literally means to lead astray. Through trickery and deception and of course sweet nectar, the orchid lures insects (or birds or bats) and in turn pollen is transferred from flower to flower. The title of the show, ‘Catfishing’, refers to this complex relationship.

The reciprocity is a complex evolutionary question. Charles Darwin was presented with an orchid in 1862 which had foot long nectaries. The only explanation, thought Darwin, was that somewhere in Madagascar, there must be a moth with a 12 inch tongue. In 1992 scientists observed the moth feeding on the flower for the first time.

The doubled image of the wasp and the orchid is found at many points in the work of Gilles Deleuze. In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari use this symbiotic relationship to explain their key ideas: becoming and de- and re-territorialization. They describe how certain orchids display the physical and sensory characteristics of female wasps in order to attract male wasps into a trans-species courtship dance, which as they write is ‘against nature’.

In this case the lure is sex not nectar, the wasp moves from flower to flower fucking and again in a secondary act pollinates the flower. Through this seduction the wasps are unsuspectingly co-opted into the orchid’s reproductive apparatus. This is exemplary of what Deleuze and Guattari call a becoming (as opposed to a clear cut being, becoming is always in a state of play). The wasp, enlisted into the reproductive cycle of the orchid, engages in a becoming-orchid. This is not, they stress, an act of imitation, but a genuine incorporation of the body of the wasp into the orchid’s reproduction.

The same is true in turn for the orchid itself, which engages in a becoming-wasp, not by copying the female wasp, but by crossing over into the zone of indiscernibility between it and the wasp in a series of de- and re-territorializations.

There is a perfect symbiosis in the paintings between the airbrush and traditional brush layering and the orchidian subject with its stains and blushes. The flowers call strongly to the visual desire in the viewer through colour and texture and beauty. The hand of the artist too is obvious in certain gestures and marks. The paintings fascinate through the controlled skill of the artist, tricking the eye, with a mixture of figuration and abstraction.

– Oliver Watts, 2021