Artworks

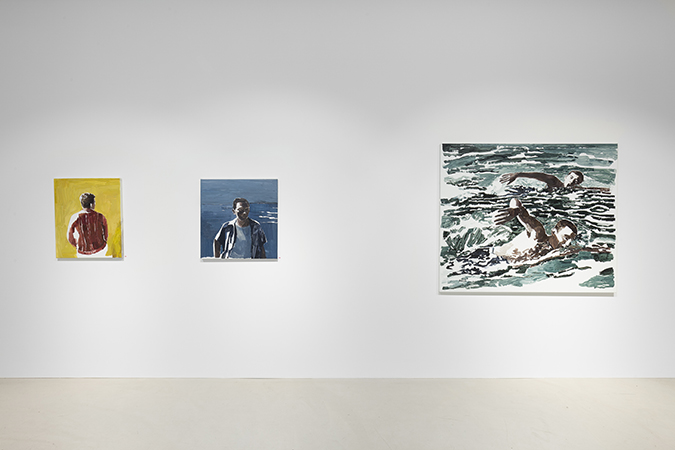

Installations

The advent of photography changed the course of painting definitively. No longer did beautiful landscapes need to be painted amid the temperamental conditions of nature. And gone were the days when you would sit for hours to have your face replicated on a two-dimensional plane. The camera could do it for you, and it could do it in an instant. Portrait sittings diminished, the importance of preserving landscapes in the name of art was reconsidered, and the role of painting was called into question. But not to its detriment, although this may have seemed to be the case at first. To assert this, we can look towards Modern Art and its innovations, yet we often lose sight of the camera as a major catalytic force behind this.

Clara Adolphs sources lost and discarded photographs of landscapes and anonymous people, and in painting them, she reminds us of this history. Harnessing painting as a form of documentation, she asks what can it offer here that photography may not?

In this new body of work, Adolphs adopts a larger scale. She states:

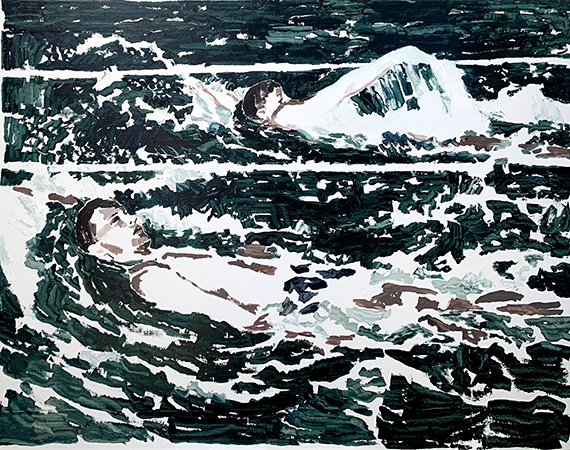

The photographs I work with are mostly very small, and in blowing them up, the figures and objects in the image become increasingly abstract, so I am required to create detail that isn’t there. But at the same time, it’s important not to get too tied down in detail.

In many artistic portrayals of the camera, the photograph is depicted as an enigma, much like a silent bystander who has witnessed something that cannot be disclosed. Michelangelo Antonioni’s seminal film Blow Up (1966) is famously reminiscent of this. The film follows Thomas, the protagonist, who has captured a lovers’ quarrel in the park. At home, he develops and enhances the scale of the photographs, and he becomes fascinated by them. He begins noticing the various arrangements of light and shadow, and he continues to look deeper until he discovers a crime scene playing out in the speckled greyscale background (what appears to be a man with a gun and a body lying on the ground). Beneath the surface lies a story here, but it asks more questions than it answers. While Adolphs’s work doesn’t deal with this particular subject matter, her practice similarly utilises photography for its ability to expose and conceal information. In blowing up the snapshot by translating it into a large painting, Adolphs attempts to grapple with all the complexities not immediately visible in its small, original form. She extracts something encoded within the image, something we can feel in our memories and experiences. Though Adolphs’s source material is rooted in the past, there is something timeless about her reinterpretation of it.

Adolphs is an intuitive painter who marks her surface with confidence and consideration. Her palette is imagined because the majority of pictures she sources are black and white. Her cool tones capture a fleeting sense, somewhere beyond the horizon. Sweeping strokes invigorate the scenes she renders, and her impasto use of colour intensifies attributes pertinent to a particular landscape, like the blue of the ocean or the frosty sky in the alps. A distinctive aspect of this exhibition is that her subjects are predominately alone and caught mid-action without warning. Some are splashing the water and performing strokes in the ocean, while others have retreated into themselves and are not aware they are being watched. There are dashes of colour placed beside multiple sections where the canvas is left untouched to indicate such movement but to also show a lapse in time. The complexity of memory lingers, and we become oddly invested in this isolated moment.

The work brings to mind Edward Hopper – the American artist of empty spaces – whose characters offer us the chance to reside within their space for a while. They too are far from home; we see them in the hotel, the gas station, the coffee shop in a foreign city. We project our craving for connection onto these anonymous subjects, but we take comfort in their solitude. In Adolphs’s paintings, we get a little closer, and then we discover these characters are familiar. Sometimes we see them in ourselves.