Interview with Amber Boardman By Stuart Horodner

Stuart Horodner

In 2019, you did a series of crowd paintings of exuberant sports and music fans jammed together. Massive Touch Network, in particular, reminded me of the countless masked celebrants in James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889. Your new paintings seem fixated on questions of choice. What do we want and why? How much do we participate and is resistance possible? Works like Dizzying Array and Style or Comfort, for example.

Amber Boardman

I think a lot about the number of decisions we make in a day. These tiny decisions—many of them screen-based—gradually deplete us as our behaviours are continually nudged by algorithms.

SH:

Let’s face it, we are exhausted by countless offerings to be considered, clicked on, and liked. Do you know Sherry Turkle’s writings? In her book Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age she argues that we live in a universe of constant connection but no real conversation.

AB:

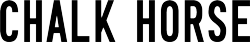

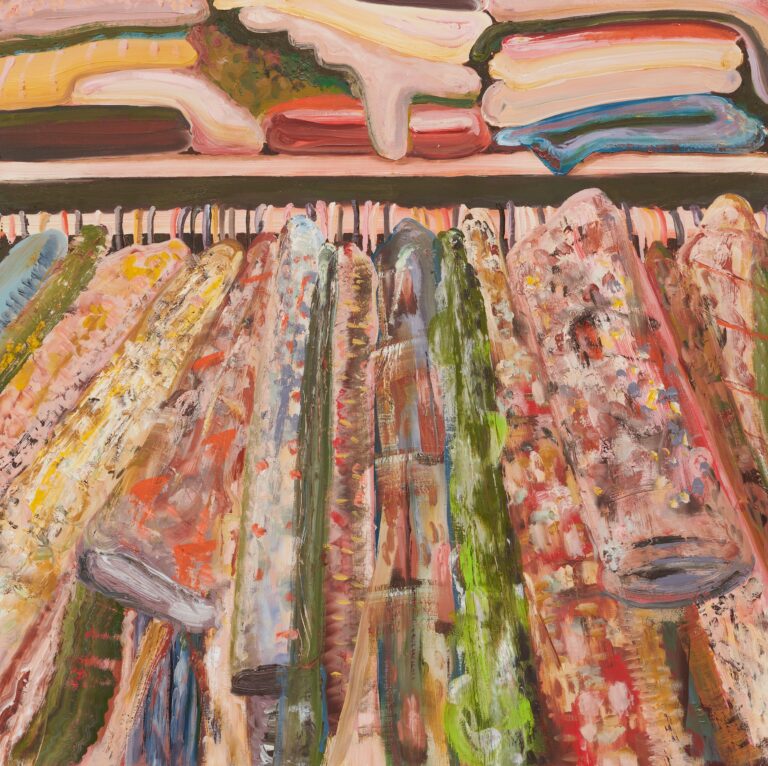

How do you solve the problem of the increasing speed of life? How do you catch the internet and pin it down? For me, painting is a way of understanding, a way of organizing and putting things away in neat containers. But I also rebel against too much structure and want to break out of it. You can see evidence of this in the grid-based works Dating App Algorithm and Porn Categories. They are an overview map of part of the internet. They’re the structure we’ve imposed on ourselves by our reliance on tech to help us decide what might titillate us.

SH:

Painting is a good form of titillation. A slow and considered one where the visual and material vocabulary can do its thing. Scene, details, ooze, stroke, smudge.

AB:

The differences between my working materials are stark. I spend a lot of time on my computer (clean grids and right angles), and I work with paint (oily, smelly, and unruly). But all of us are simultaneously dealing with neat and tidy binary code, and the messy human elements of people, bodies, and personalities.

SH:

I appreciate the childlike vision that mixes the real and the imaginary. Dreaming up personal desires and civic ones. Constructing a stage and moving everyday action figures around.

AB:

I am definitely playing in that space. In Movie Night, it’s the perspective of a viewer who can see beyond the normal visible light spectrum, into the range of algorithms, Wi-Fi, or broadcasted information moving out into the room. In Dream Home Renovation, someone’s vision of home being renovated to suit a luxury beachfront fantasy was made from referencing both a 3-D model and my imagination. I had several maquettes made of these paintings in order to turn them around and see them from all angles.

SH:

You create depth and then flatten it. You weave simultaneous time and overlap different codes.

AB:

An invisible system running things in the background is what I was thinking about in Civil Planning. This work concerns decisions around plans for a city, its underworkings and the structures that keep it functioning. The pipes on the building were made to resemble the interconnected circuitry of a microprocessor. I’ve loosely referenced Google Street View images of buildings and city dwellers on their morning commutes. My imagined interpretation of their screen-based mental states ripples out into the space around them.

SH:

Our internal anxieties and frustrations are so available, right?

AB:

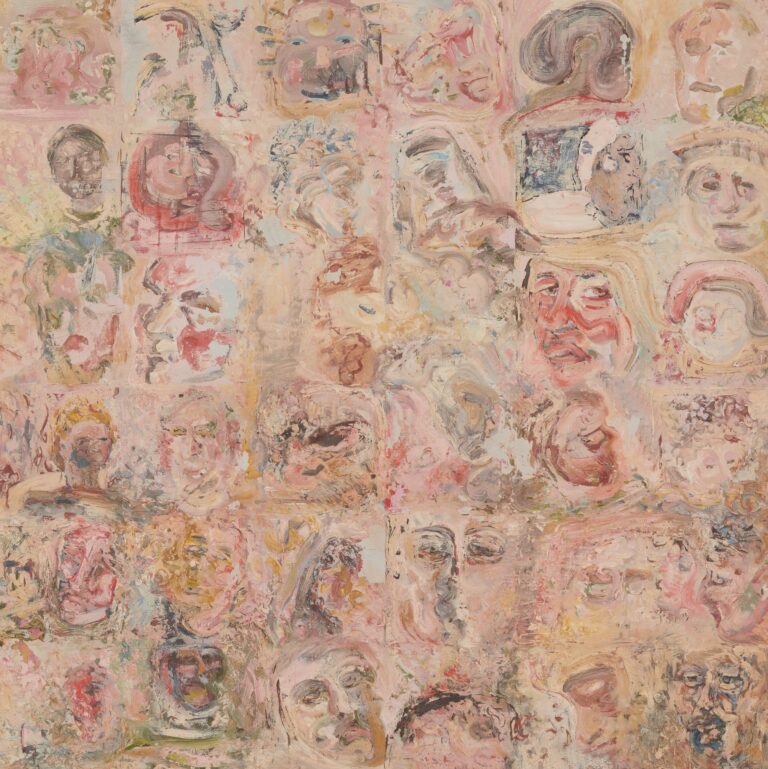

Absolutely. In addition to the macro concept of decision fatigue in everyday life, these works are also about the process of painting and the thousands of tiny decisions I have to make as an artist. One of my rules is that my workday in the studio is only finished when I’ve run out of paint on my palette. Paint Shelves is a record of this part of my process, in which remaining bits of paint are used up or ‘put away’ on these shelves before the day is over.

—

Stuart Horodner is Director of the University of Kentucky Art Museum. His art writing has appeared in publications including Art Issues, Art on Paper, Bomb, Dazed & Confused, and Surface.