Artworks

Installations

When Hong Kong was reclaimed by China in 1997 it was a very different place from the barren, mountainous island it had been prior to British occupation in 1842. It was one of the first parts of East Asia to undergo industrialisation; it became a city of skyscrapers and a place of business with a major bustling port. Industrial architecture often informs Jasper Knight’s practice and in Elevator Music it seeps into the work in a similar way, but it takes on a new geography. Here, the built Australian landscape is no longer the centrepiece, it is the city of Hong Kong.

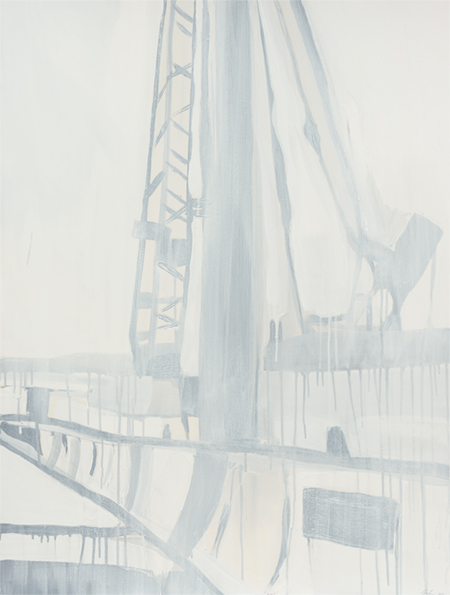

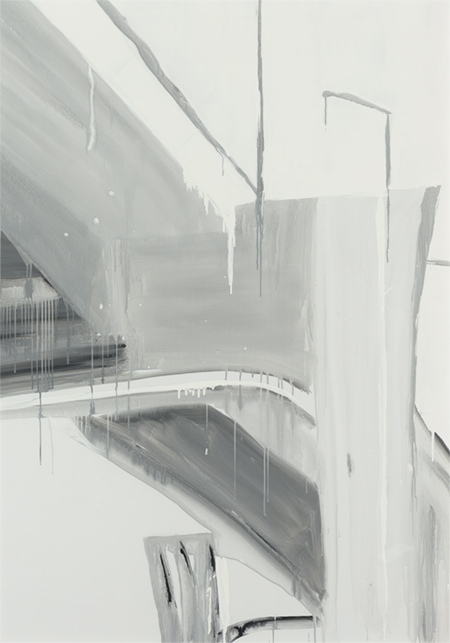

The paintings in Elevator Music are based on a suite of photographs Knight captured from the window of a taxi travelling from the airport to central Hong Kong. The photographs – incidental and spontaneous – are humble recordings of a space that could only be swiftly experienced. As the car moves, it loosely writes the poetry of the city, garnering an overall feeling and aesthetic of the place. This recalls Jim Jarmusch’s film ‘Night on Earth’ where the trailing of the taxi paints each city and its particular narrative. Maybe Elevator Music is Knight’s extension of this and Hong Kong is the 6th destination. However, unlike the characters depicted in the film, Knight’s driver didn’t speak a word and instead turned on the radio, allowing elevator music to fill the void. The steady silence in the car may have occurred due to the language barrier between Knight and the driver or perhaps, was the result of the familiar, meditative quietness driving sometimes incites. Though, through this silence, we can imagine the passenger switching to a passive, contemplative role, while the driver concentrates on the task of navigating the city as he anticipates the turns before they appear, using his experience to find the fastest route possible through the labyrinth of streets. To the passenger, these same roads are exhilarating and loaded with first impressions; when overcome by a tourist’s romance, the snapshots captured through the window reflect back these fresh visual encounters. The painting ‘White Noise’ alludes to this as well as the city sound of Hong Kong, where a constant and inescapable hum permeates through the hazy city smog. Knights paintings, with their paleness and effortless washes of white, contain a muted, kinetic energy.

For this series, Knight leaves his distinctively bold and primary palette behind. Emphasis is no longer created through the use of vibrant colour, now the artists hand and draftsmanship commands attention. Line becomes more apparent, accentuating the rigidity of the buildings and the crisscrossing of scaffolding. The limited palette, predominately white and laced with grey, evokes the moody polluted mist of Hong Kong. It is like a filter or a lens bathing the structures, bringing out their tonal qualities, and spreading a diffused, ethereal light across the surface. In 1961, composer John Cage famously referred to Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘White Paintings’ as “airports for lights, shadows, and [dust] particles”. Knight’s paintings are like this – from the airport to the city they collect light, shadow and the floating matter scattered through the air. Knight also continues the lineage of Rauschenberg through a persistent use of assemblage and by a diverse range of media. In Elevator Music there are works on board, aluminium, corflute, and cotton paper and each medium facilitates the work in its own unique way: aluminium allows for a smooth and unblemished application of paint, corflute catches the paint as it drips while letting lines run more vertical, gloss acrylic creates a sheen reminiscent of the Hong Kong skyline, and cotton paper (which requires a more delicate touch) helps to emphasise the softness of sky.

Through this strong, physical connection to subject combined with a reductive approach to colour and composition, Elevator Music presents a view into a fast-paced, industrious city, via a lens that is still, soft, and intriguing. Knight proves that in silence you can still find inspiration, you can even capture a city without colour…. all you have to do is look out the window.

Elle Charalambu, 2019