Artworks

Installations

Epoch

In Harry McAlpine’s Epoch, we encounter a world in black and white. Moving through the exhibition, it’s easy to assume we’re looking at strange, prophetic photographs: Various fabrics and textures are depicted with the sharpest detail, the subtlest reflections are captured, and the most dazzling concentration of light is evoked, as is the deepest, inverted blackness. We notice recurring black boxes and cardboard boxes with holes for eyes; plastic masks, plastic flowers and atomic bombs; tiny twig-like trees around barren landscapes and delicate hands creeping out of the sand. McAlpine is an image-maker. His compositions linger, and every one of them is realised with charcoal. Here, he has the future in focus with recognisable parts.

Avatars for a virtual world

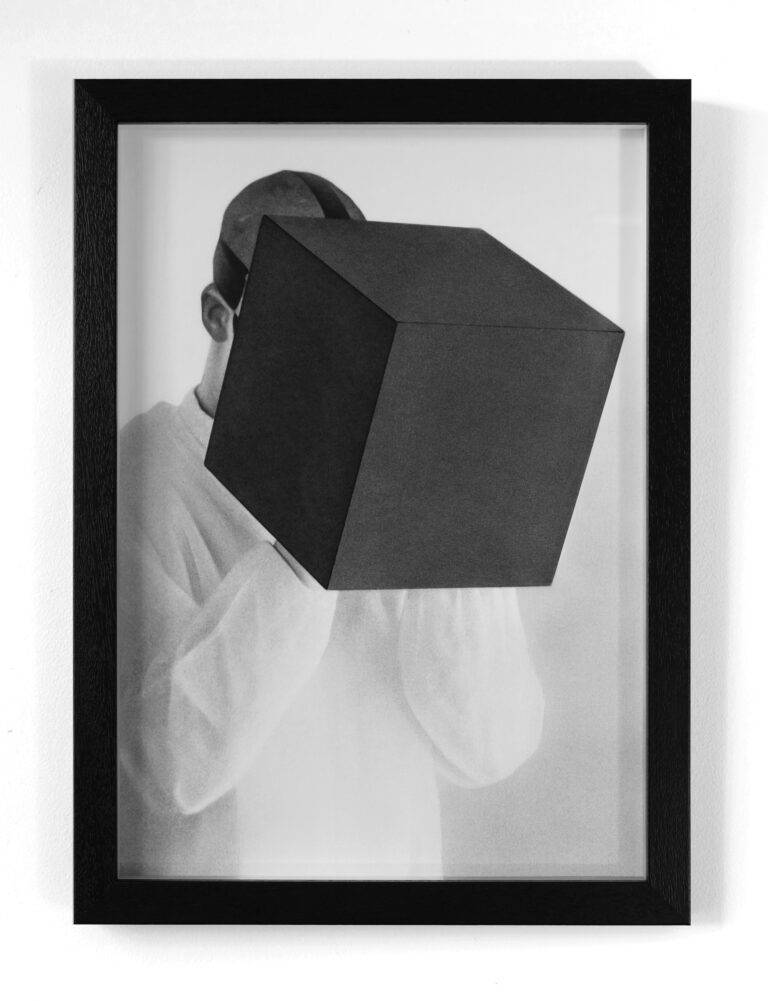

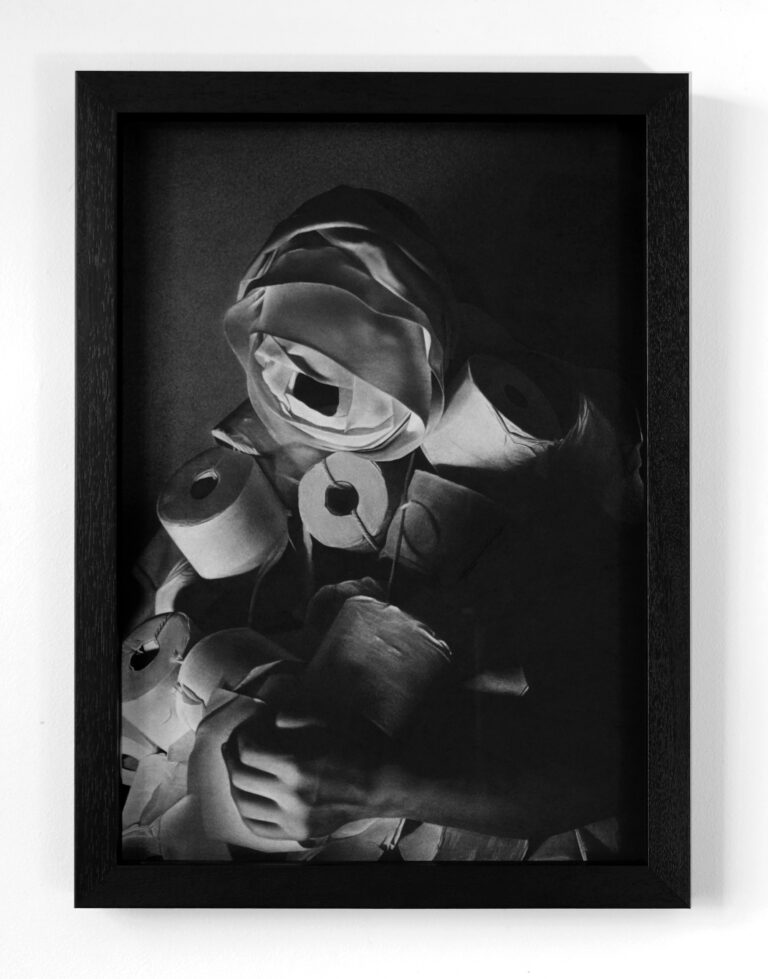

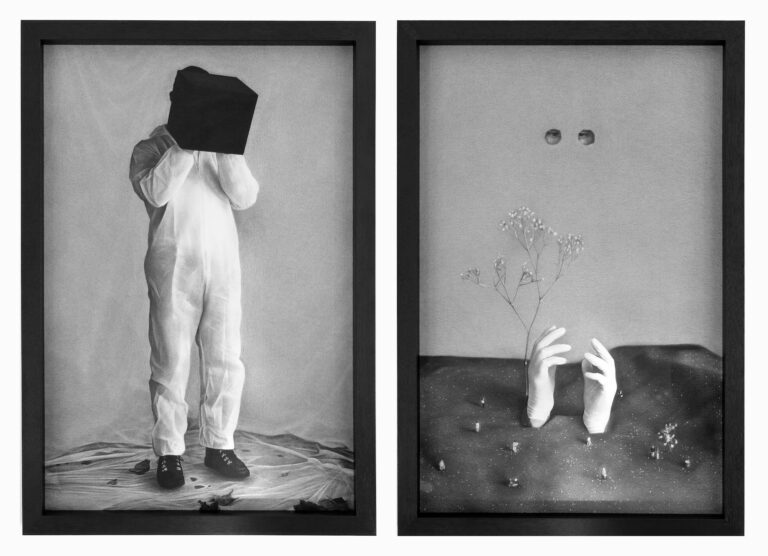

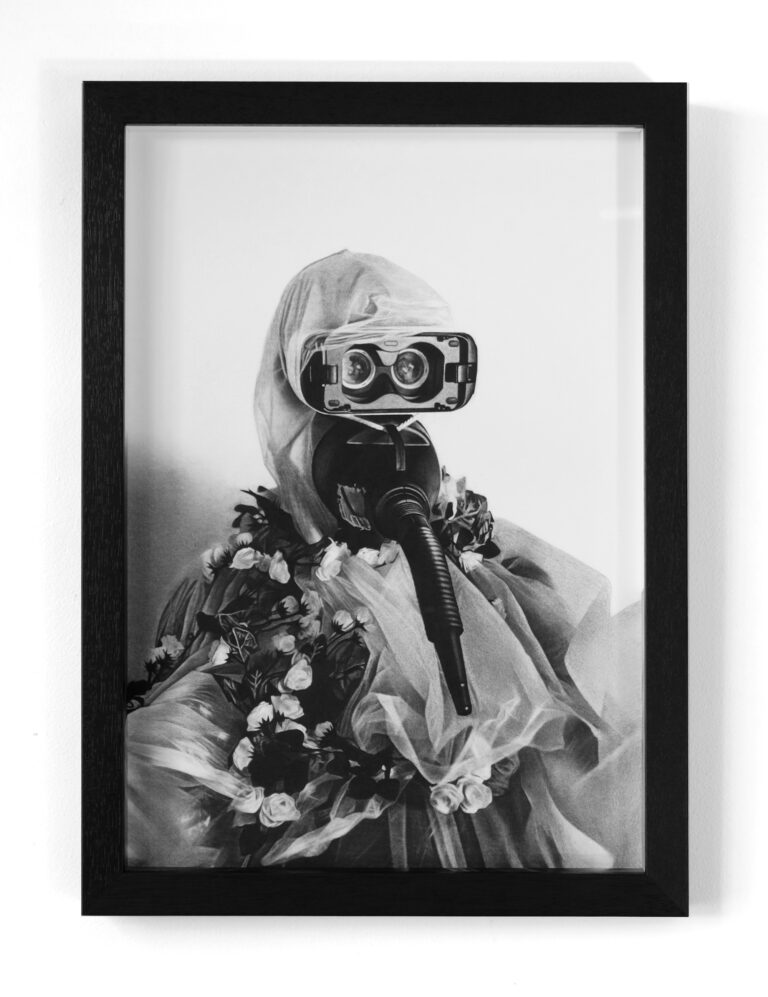

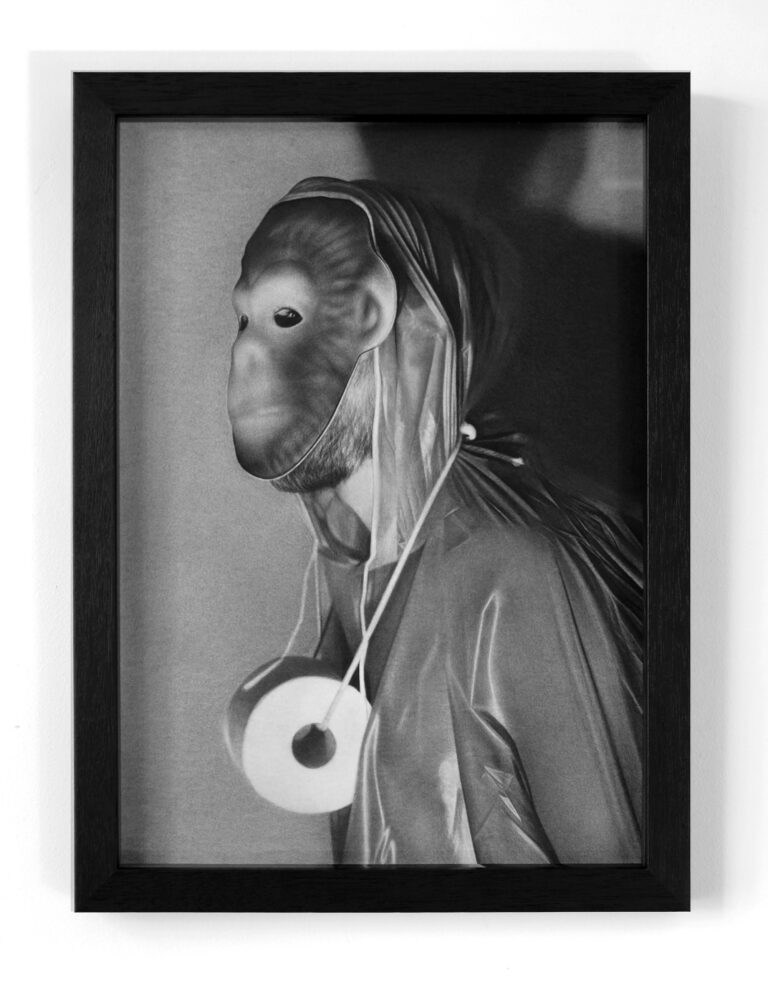

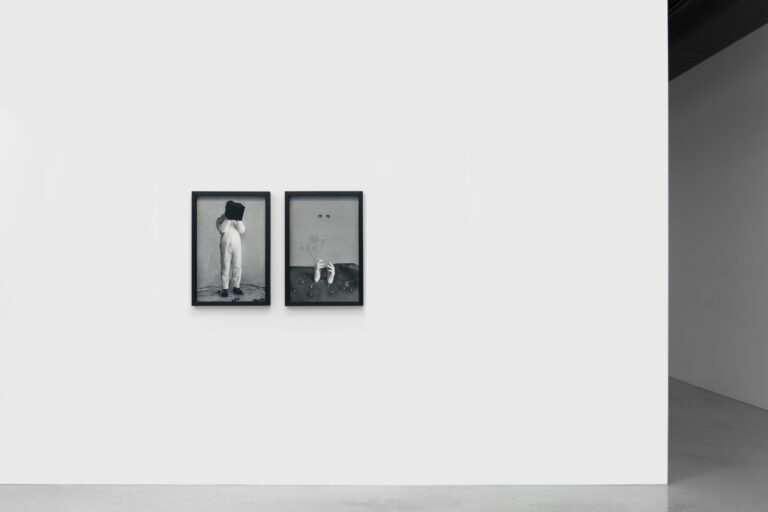

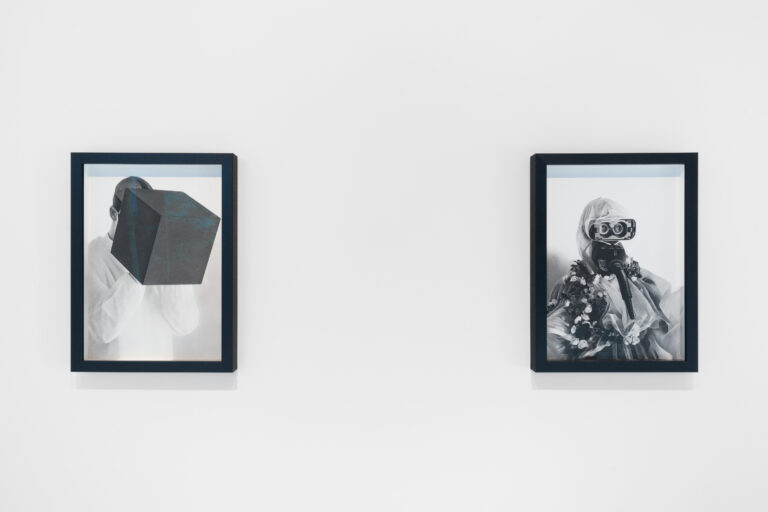

In Epoch, there are three kinds of images – the first, consistent in the artist’s practice, are the portraits where McAlpine often uses himself as a base, loading various articles onto the body until any recognisable part of himself becomes concealed. The eyes are veiled or only just discernible behind the open hole of a mask. A new character emerges.

The portraits possess a theatricality where comedy and tragedy occupy the same space. We see it in the shoddy attempts at protection: ‘Plague Doctor’ sits cloaked in two-dollar shop trinkets that attempt to form a hazmat suit. We see it in the tragedy, the desperation, the confusion and the conviction. ‘Cyclops’ depicts a figure shielded by so many rolls of toilet paper that they morph into a towering monument of the product. I’m about to deem this hyperbolic, but I recall a meme circulating the internet of a woman stockpiling an entire garage of toilet paper. However, in Epoch, the absurdity seems more subtle. The figures are bestowed with dignity and grace. I experience feelings I can trace but can’t fully find, like astonishment and an obscure melancholy when observing works like ‘Monkey Brain’.

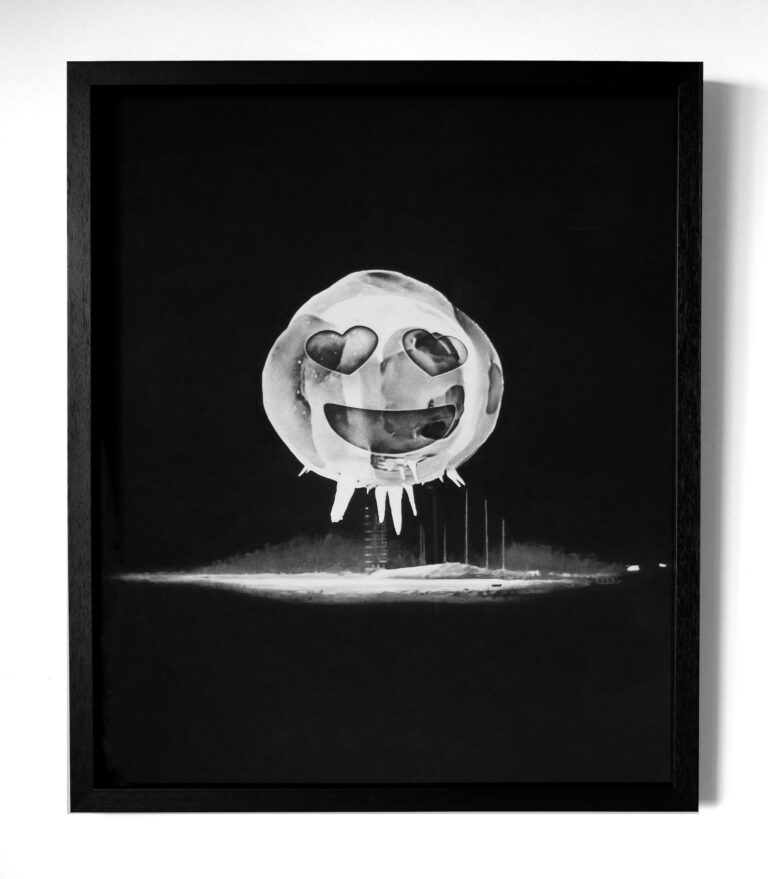

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

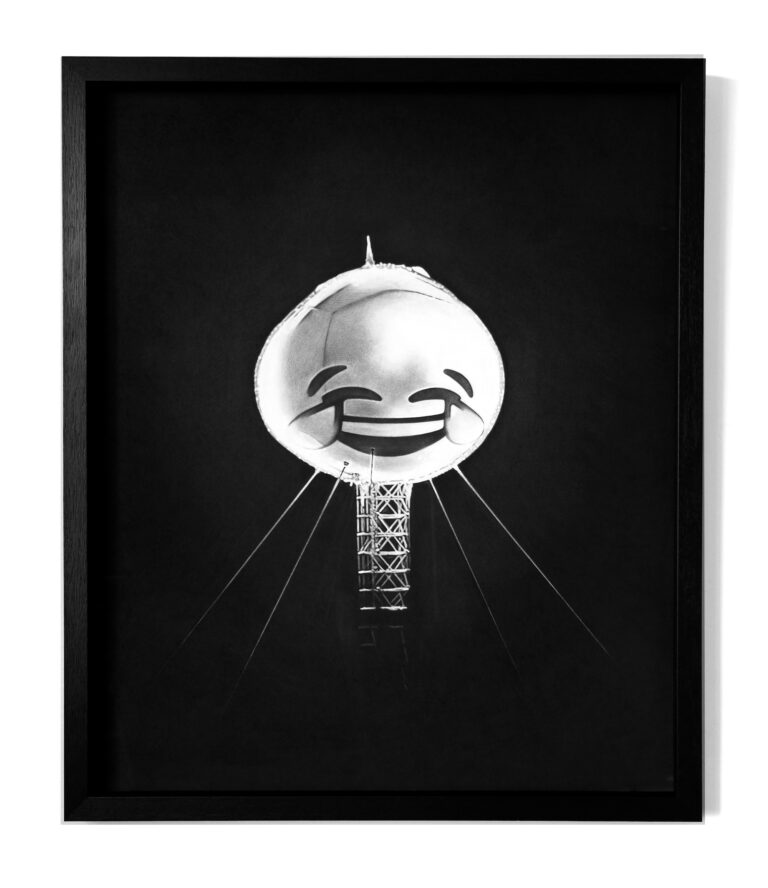

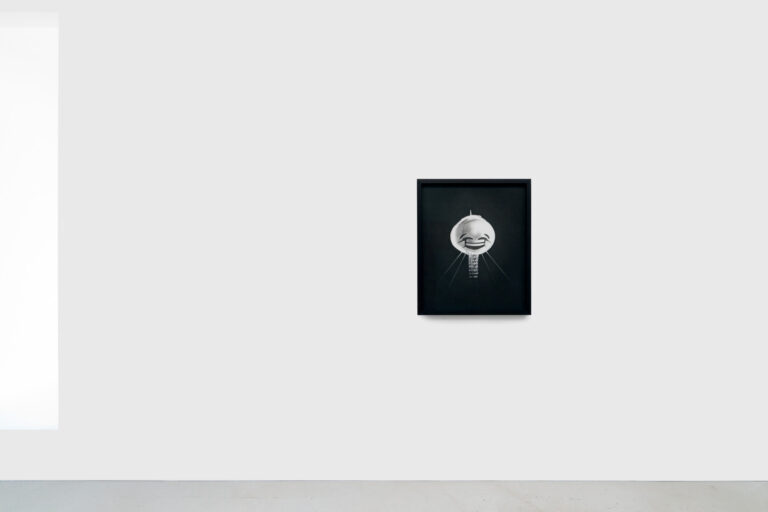

Looking at ‘ROFL’, ‘LOVE’ and ‘Dead’, I can’t help grinning with a suppressed shudder. Humankind creates technology in the name of progress but threatens to destroy everything with the same technology. Meanwhile, someone says something mildly amusing on Instagram, and the receiver follows up with a ‘Dead’ emoji (eyes crossed out on a face) because it’s ‘so funny. Emojis have replaced words, and they don’t even mean what these words mean.

The Garden

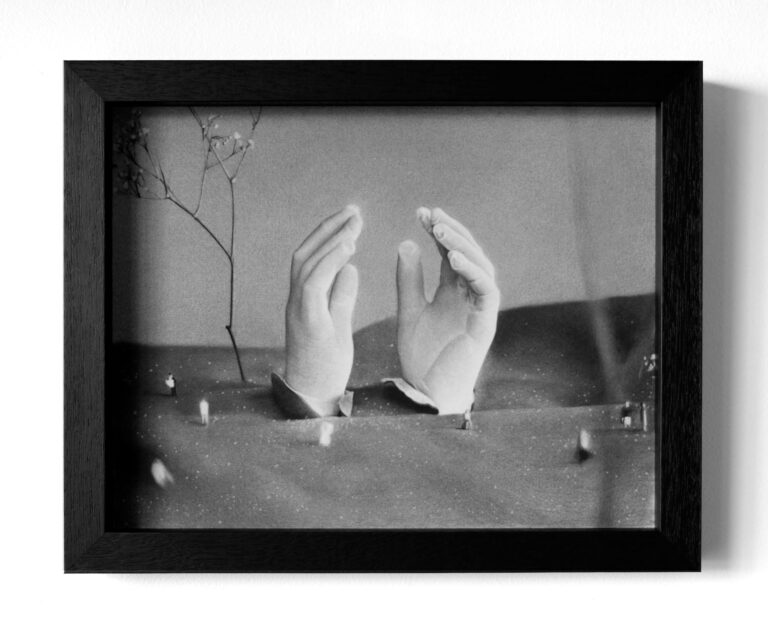

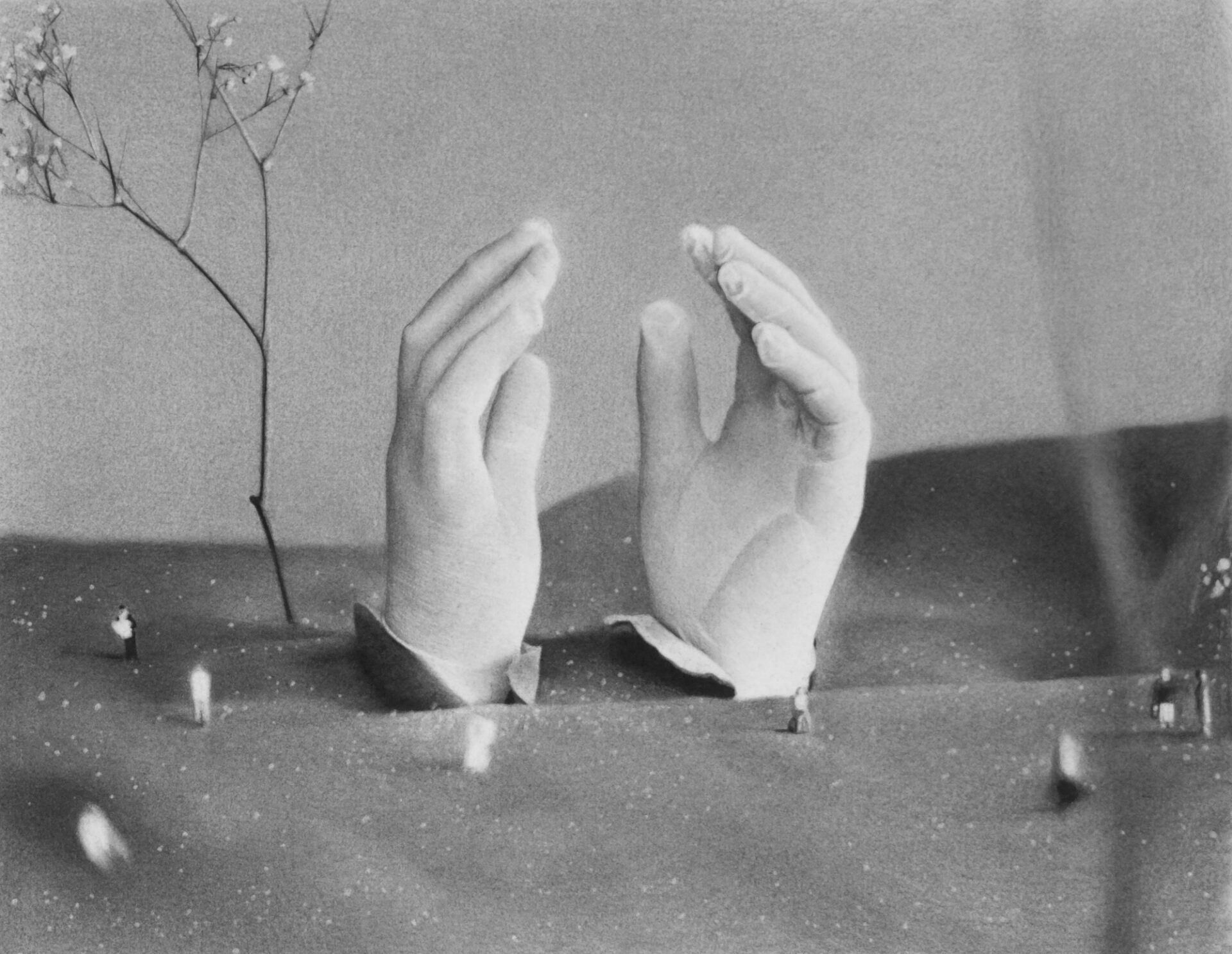

In ‘IRL & the Garden’, I imagine glimpsing through a crack, looking into the next few decades. The inevitable entropy of our natural world and the emergent virtual one. In the right panel, ‘The Garden’, a stem of baby’s-breath imitating a tree is propped up in thick sand, and miniature people are scattered around the landscape like those in a Bruegel painting. Here, an uncanny synthetic feeling overrides the enticing initial ‘naturalness’. While ‘IRL’ (the left panel) appears desolate and fruitless, there are traces of existence – realness on its side. Crumpled leaves look like they’ve been swishing along the floor; the plastic drape is so visceral you could almost feel its touch on the skin. McAlpine tells me he suspects that if a utopia exists in our future, it will likely be a virtual one embedded in the dystopia of the reality we seem to be building ourselves today.

When I first saw McAlpine’s work, I was reminded of the novel Underworld (1997) 1 by Don DeLillo: an epic story weaving history and narrative together as it moves through the second half of the 20th Century into a virtual landscape. I remember a character driving through NYC thinking, “…it’s as if the billboards were generating reality”, and another convincing himself that “History was not a matter of missing minutes on the tape. I did not stand helpless before it.” The real America is depicted as a sublime junk heap. Lines like “There is a balance, a kind of standoff between the time continuum and the human entity, our frail bundle of soma and psyche” and “that’s creation out there, little green apples and infectious disease” are scattered throughout. Lenny Bruce at a gig during the Cuban Missile Crisis, screaming and laughing, “We’re all gonna die!” Exclaiming, “This event is infinitely deeper and more electrifying than anything you might elect to do with your own life. You know what this is? This is twenty-six guys from Harvard deciding our fate”. All the seriousness taken lightly and the absurd taken seriously. The surrealness of human existence.

Epoch emits a holy echo. A solemn glow emanates from each drawing. The present and past rolled into a vision of the future. How? From nothing but stardust. Let the stream of consciousness subsist. Consciousness. And let out a laugh.

Monkey Brain.

Elle Charalambu, 2022

__________________________________________

References

1 Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, directed by Stanley Kubrick (produced by Stanley Kubrick distributed by Columbia Pictures: 1964)