Artworks

Installations

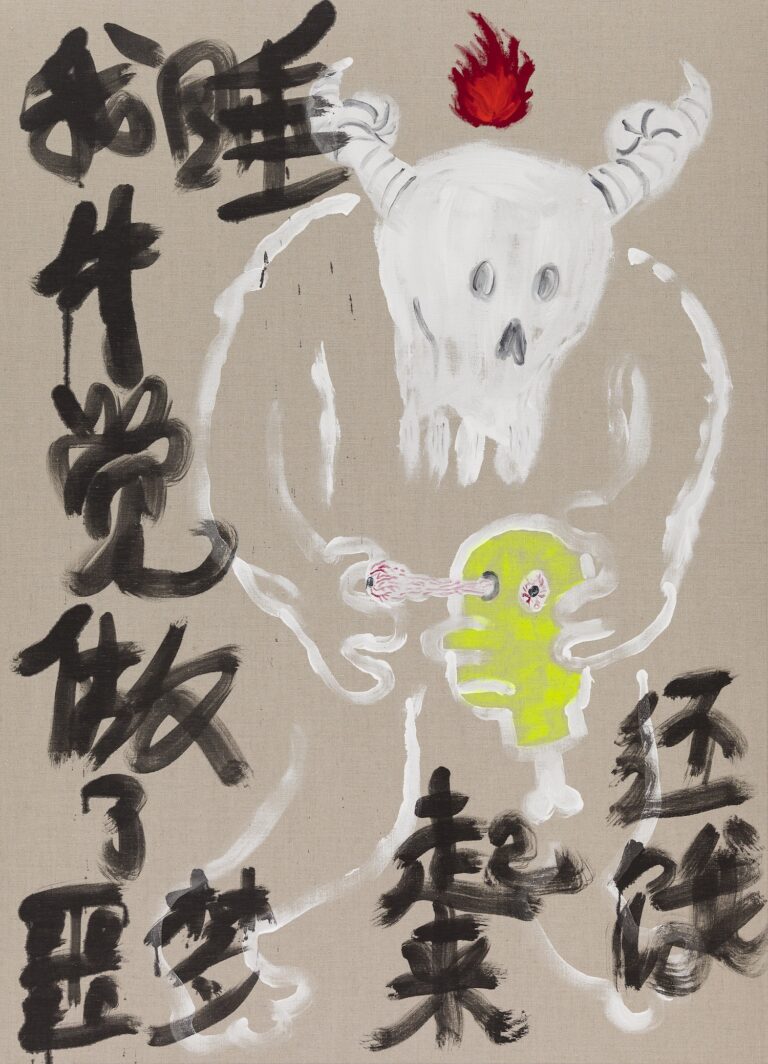

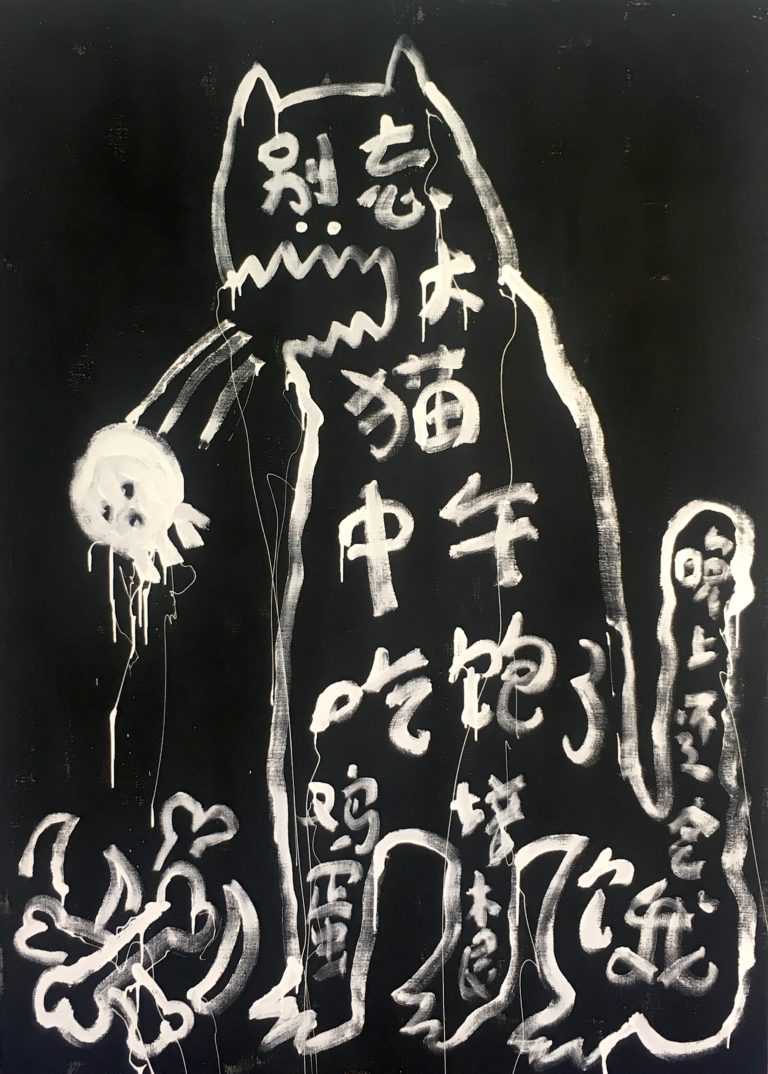

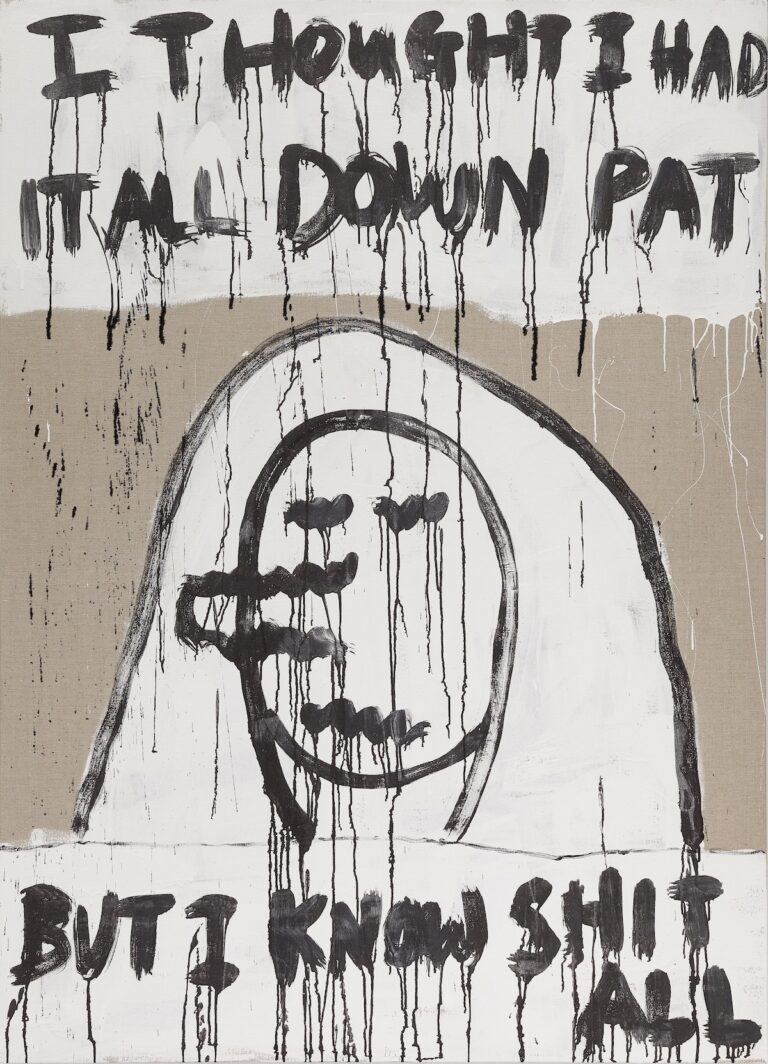

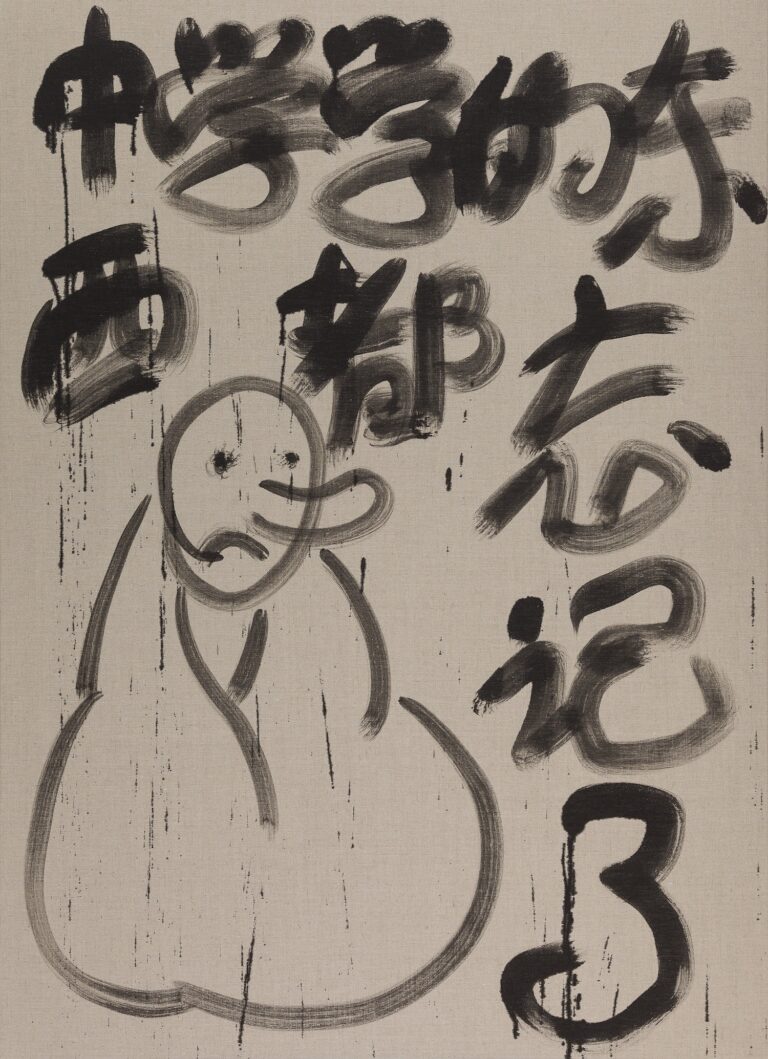

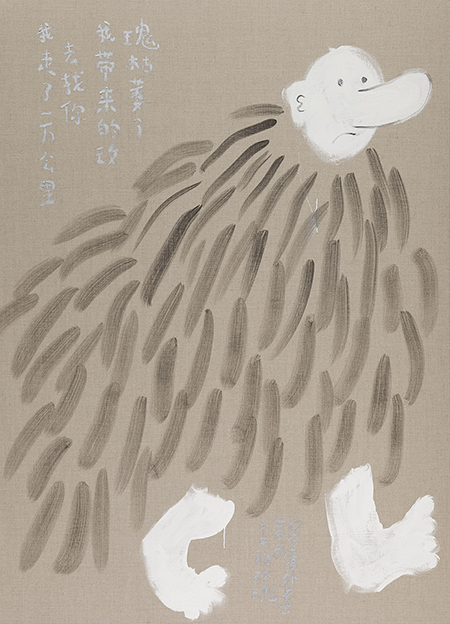

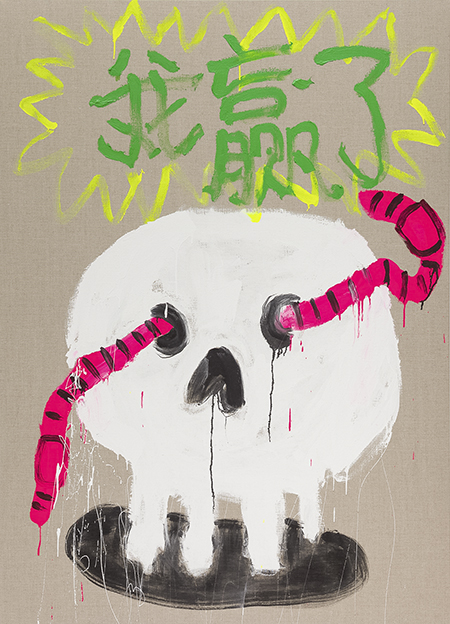

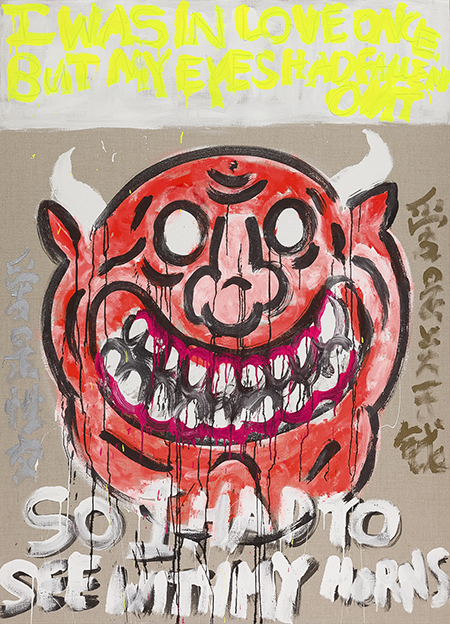

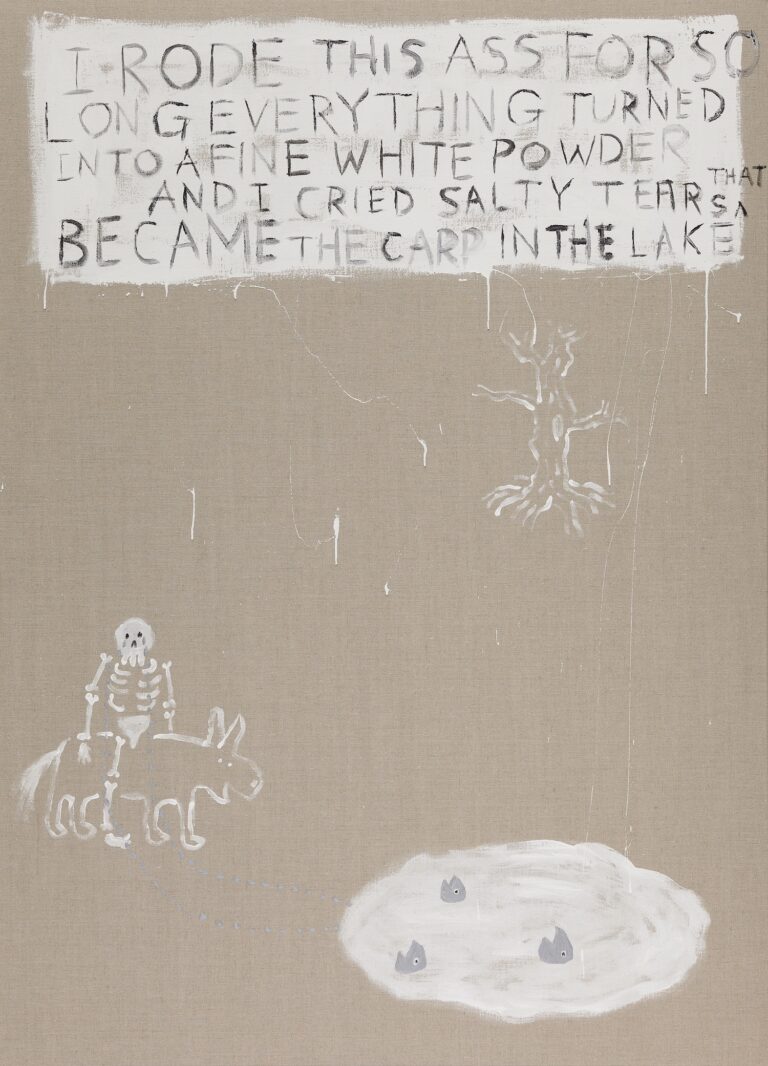

Here we see what appears to be Phu’s familiar cartoonish figures, satirical text and whimsical lines, usually found sprayed directly onto walls, drawn on paper or scrawled on black plastic. Like the drawings and paintings before them, they lay exposed on an unprepared surface, this time it is a naked linen making claim to a certain honesty – a certain spontaneity, and a trace of unencumbered movement.

We know of course that Phu doesn’t really work in this way, well at least not from beginning to end. In fact, preparation is a large part of his work, he may work through a number of preliminary sketches before arriving at a composition he is happy with. Even then there is a lot of negotiation, examination of the canvas and gesticulation before he commits to mark making. His approach, with sketch in hand, or pasted on a nearby wall, can be likened to that of a high jumper, he marks out his approach in a very calculated way, drawing on his past experience, he moves closer, moves away, visualises and finally, summoning his bodily memory, makes the leap- once in the air, the conceptual part of the work turns into action and he doesn’t stop until the work is done. This analogy with the athletic high jumper might all sound a bit heroic, but it is the reality of all artists, whose main game is to put themselves out there at the risk of criticism and failure.

These paintings have the graphic impact of billboard posters and a compositional logic that resonates with the vernacular of heavy metal T-shirts on the one hand and Chinese ink brush paintings on the other. Where a T-shirt emblazoned with tour dates and the usual macabre band insignia might be worn in memory of a past event and a public declaration of a counter- culture, Chinese ink brush paintings offer a figure in the landscape often accompanied by a poem or a wise proverb and enjoyed in a hope that it may offer a better understanding of our relationship to heaven and earth. Phu’s paintings partake in both worlds. In the vein of heavy metal they are loud and energetic but are full of self-loathing, and within the lineage of Chinese brush painting they are reflective and poetic.

Phu enlists demons, skeletons and goblins as personifications of anger, confusion, stupidity and moral bankruptcy and gives them a voice through text, as the words drip, are squashed, stretched and skirt around the edges they become image.

We are left with anecdotal accounts of life, personal, funny and sometimes sad stories of childhood, teenage angst, and adult life that are a welcome relief to the dogmas of political rhetoric and monolithic certainty of some social commentators and cultural organisations that populate our daily interaction with the world. Ultimately, they are striking in their witty expression of the human condition and remain enjoyable to look at.

Dr Matt Cox, 2019