In the mid-nineties, in student rental houses, there was an image almost as common as a Pulp Fiction poster. It was Jean Guidard’s 1989 photograph of the La Jument lighthouse in a storm, near Brittany, a sole lighthouse keeper at its door, in mortal danger, as a terrible wave crashes over the tower and threatens to wash him away. The print literally sold in the millions, most commonly as a poor quality photo pasted directly to a hardboard substrate, and the corners were always a little fluffy.

You would stare at the image wondering how it was done, thinking that surely there must have been some manipulation (in an Australian context, Frank Hurley-style). It seemed that no built structure, especially one of bricks, with quaint little domestic windows above the door, could withstand the weight of that water. But it was a real moment and it seemed to sum up humanities often farcically lopsided relationship to the ocean.

As the story goes Guidard was out storm chasing, quite professionally one could say, with a kit that included good lenses and a helicopter. As he had his pilot manoeuvre above the lighthouse, the lighthouse keeper, worried already that this might be the storm to bring the lighthouse down, assumed that it was a rescue chopper. He came out to investigate and that is when the shot was taken.

The risk to his life was absolutely real, and he went back through the door just in time. In an interview he said, “If I had been a little further away from the door, I would not have made it back into the tower. And I would be dead today. You cannot play with the sea.”

In the photographic moment, back in a warm house in Sydney, the water surrounded the lighthouse, its threat dissipated by frozen time and the knowledge that in the end the lighthouse keeper was safe. The fearful image transformed into a talisman and an inspiration to acts of sublime heroism.

The lighthouse and its keeper represent the isolated duty and responsibility of a sentry, keeping watch over the safety of others. Above a cliff the building assumes the angst of a Romantic seer, staring out to the horizon. Or alternatively like La Jument, within the water, standing strong, as the waves incessantly envelope it, it seems to suggest the tantric unity of a Yoni-Lingam.

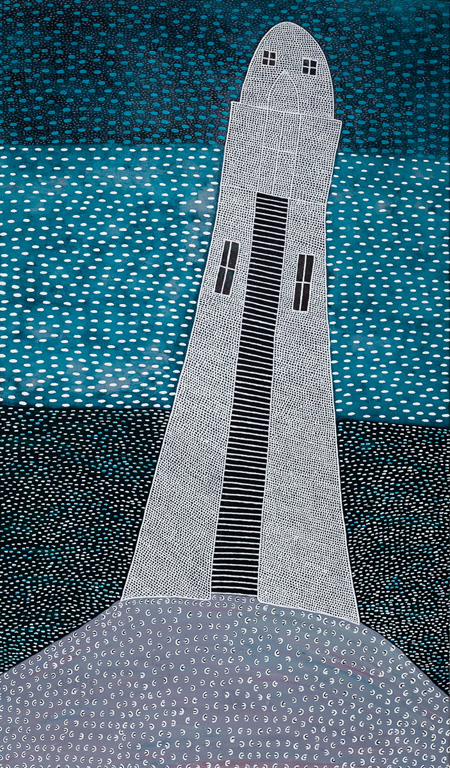

Both Jasper Knight and Clifton Mack share the lighthouse as a recurring and important subject in their oeuvre. Knight was born next to the harbour in Sydney and the lighthouse is a personal memory as well as a cultural icon. In these works he seems to deconstruct the engineered efficiency of the building, humanizing them and turning them into existential metaphors of loneliness, service and possible weakness.

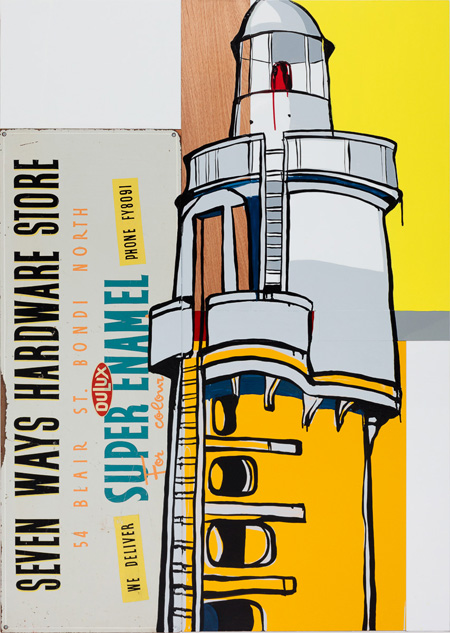

For Clifton Mack the lighthouse is also paradoxical. The Jarman Island Lighthouse is now ruined and inoperative. Regardless it still functions as a tourist attraction and the site of community events. It represents colonial power and disenfranchisement, cartographic violence as well as pioneering ingenuity (it is a pre-fab cast iron structure held up by 5 stays shipped with great skill to this far flung part of Empire).

Although the pharologist, like a strange maritime trainspotter, might take the love of lighthouses too far, there is no doubt that this beacon of light on the hill is an important marker for our relationship to nature and to society. As the lighthouse becomes more and more useless, superseded by GPS and other navigational technologies, it will be liberated more and more as a poetic symbol and muse to artists.