Artworks

Installations

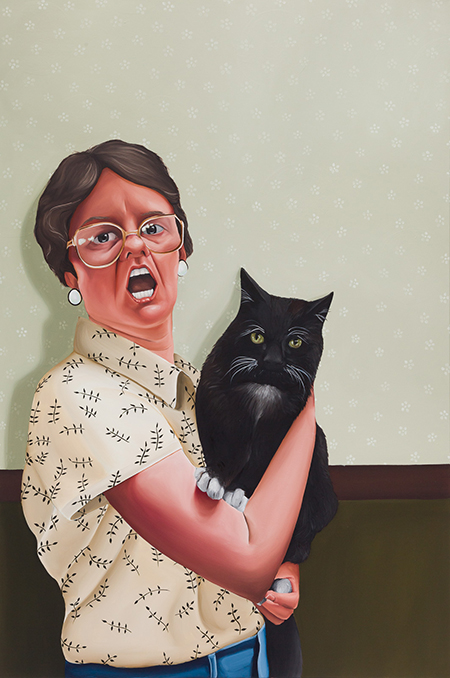

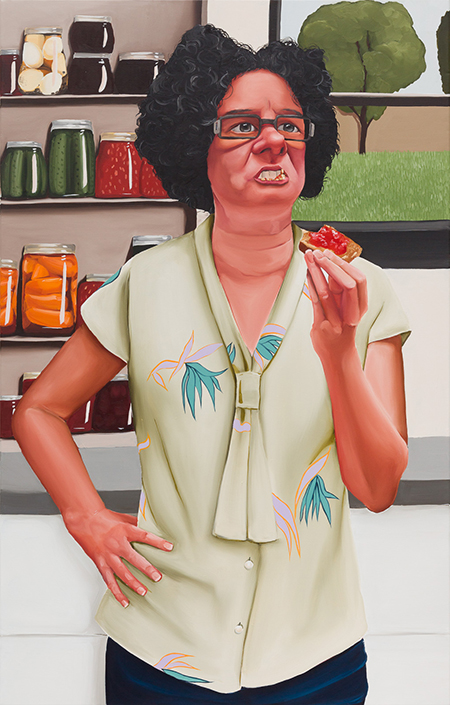

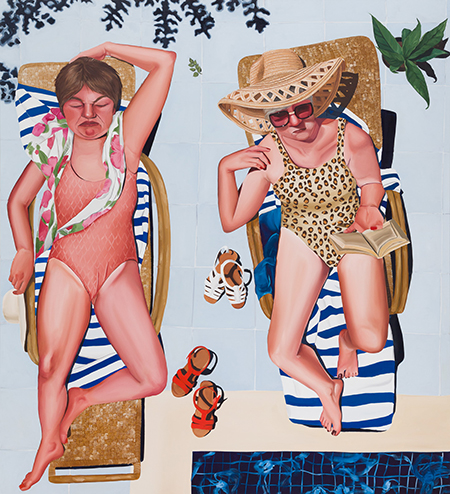

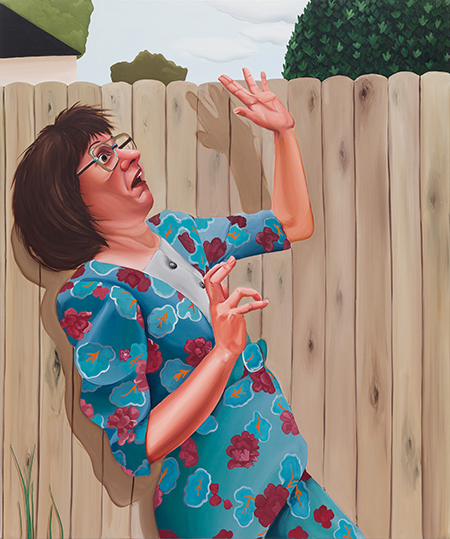

From a small studio shed, making art is a way of understanding and knowing the world: choosing and e-buying dated fashions and wigs; painting and scrutinising the details of a plant from life; studying your face contort to unnatural expressions in a mirror; searching endless images from peculiar sites on the internet; drawing cartoonish figures and scenarios; staging and photographing self-portrait tableaux with a camera timer. The whole process of painting for Madeleine Pfull is a way of intensely grappling with the anxieties and joys of life.

In this show, and for some time, Madeleine has made herself a middle age, middle class, older woman. As she expressed herself in an artist statement for Nino Mier Gallery last year:

Dressing and ageing myself to create characters has become an integral part of my process. I am exploring my many potential futures, which terrify and fascinate me.

These works are not masks, aping and laughing at her subjects, but a self-reflective mediation. It would be wrong to only see Madeleine’s work as grotesquery or caricature. If the artist has an almost singular ability to be both an insider and an outsider, Madeleine’s work has a proximity to her images of women that the critical distance of satire does not.

In Sao Lady I and II the paintings embody the dry plainness of the biscuit, allegorised by maybe a teacher in a common room or a worker in an office break out. The monochrome in beige, doubles and triples the banality.

The women in Madeleine’s work are a form of marginalised subject in the heart of white Australia. What these paintings involve themselves in is a politics of visibility. The difference between the visible and the invisible is one of the most important questions of contemporary society. For Jacques Ranciere aesthetics is absolutely the realm of politics. Tim Wu characterises our economy as one also centred on attracting eyeballs which he explains in his wonderfully titled book, The Attention Merchants: The epic struggle to get inside our heads. If people still dare to question what celebutants actually do, all they need do is precisely stay in your feed.

What we are all seeking is a legitimacy to our inclusion in society, its politics and the economy. But who decides what is seen and what is not? Middle aged women, as Madeleine fears, are the epitome of the invisible. In these paintings whether in the private space of the kitchen, office, garden, or pool, these subjects are not presented in social, public space; they are hidden away in small private rooms, in suburbs far from the centre. Their plainness is a long way from the chiselled modelling of insta-models prepackaged to appear only on screen, and somehow monstrous in real life; 1 million virtual followers are, for all intents and purposes more important than 5 people in the room.

Subjects become meaningful or important only as society confers meaning or importance upon them. Madeleine’s paintings are a form of resistance or insistence on a renegotiation of the terms of reference. Part of the pathos of these works is that as a celebration of the nobody, wrought now in oil painted portrait, in a high style, some at full length, they can only ever represent a radical insurrection rather than whole-scale revolution.

Madeleine’s approach in this political game of aesthetics, is to move between art and non-art, between high culture and low, between the past and the newly contemporary. They speak to a broad attack, while utilising some classic genres (the portrait, the bust, the conversation piece, the still life) as the fighting field. The work highlights that taste emphasises certain values while hiding others, that it elevates some to the detriment of others.

The master work, Pip also brought Pavlova, presents three staring subcultural critics, posed and poised, with the intentedness of any snobby high class critic; here though the quarry is the mores surrounding Pavlova. The work always confuses and equivocates. Is the beautifully painted patterning of the dresses and coats meant to spark derision? Somehow though in these paintings even that kitschness keeps together in harmony.

Madeleine activates high art motifs too to undercut the quotidian evenness. In the Sao series the Van Gogh on the wall represents the ubiquity of an image that now as a cheap print has lost some of its power. But on the other hand repainted, back into oil, reclaimed by Madeleine it allows its original resonances to reassert themselves. For Van Gogh, through his own pastor father, the sunflower represented the hope of the sun’s light, which he thought a metaphor for Christ’s love. It is this stretch, held at tension, across transhistorical ground, across social stratas usually held apart, across painterly tropes also not seen together, from which Madeleine’s work derives its frisson. The works absolutely sing on this tight string.

Hers is an aesthetic that refuses to see the ordinary and everyday as meaningless. It is an art that reconfigures, revisits, and reinvigorates. She is able to show through her zero sable brush, as it patiently iterates blades of grass, that nothing is insignificant or inferior. Her paintings engage in the politics of images, and the power of surfaces broadly, and assert the humanity of the invisible woman more pointedly.

Dr Oliver Watts, 2019