Artworks

Installations

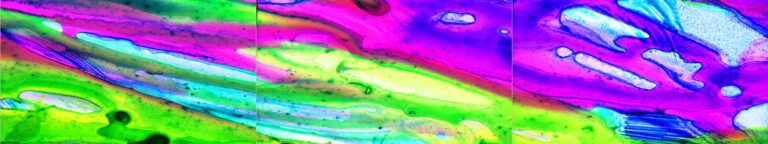

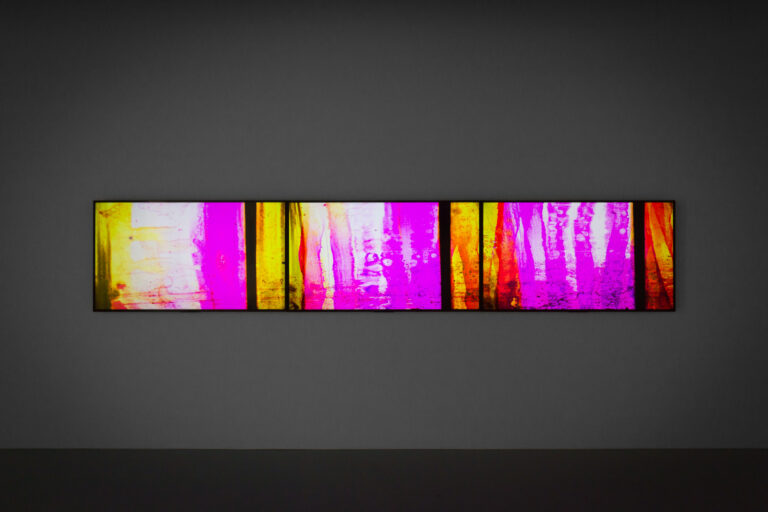

I love ‘Technicolor’ and all the different colour film processes that have been created over time. What I’m doing is more like ‘Tara-colour’ by making my own versions and making my mark on celluloid.

The great irony of Tara Marynowsky’s film work is how it is deeply invested in the mechanised printing processes by which early colour cinema came to be known, and yet, her interventions introduce – with great love and violence in equal measure – the inventive trace of her own hand. ‘Tara-colour’ – as she has named it.

A collector at heart – and with great heart – Marynowsky finds her material at sites like eBay, a treasure trove of old media relics for jostling collectors. Over the last few years, she has specifically been collecting 35mm film trailers. And not just any trailers. To appeal to her collecting framework they must abide by a particular theme or trope.

With her earlier film series, Coming Attractions, commissioned for The National 2019: New Australian Art at Carriageworks, Marynowsky was obsessed with nineties Hollywood film trailers with strong female protagonists. Beloved films of her youth (among them Pretty Woman and Indecent Proposal) are ‘defaced’ with a scalpel and watercolours as the artist scratched and hand-coloured the female leads. The outcome is a feminist response to problematic representations of the past created against a political backdrop of misogyny and violence still rampant in the present.

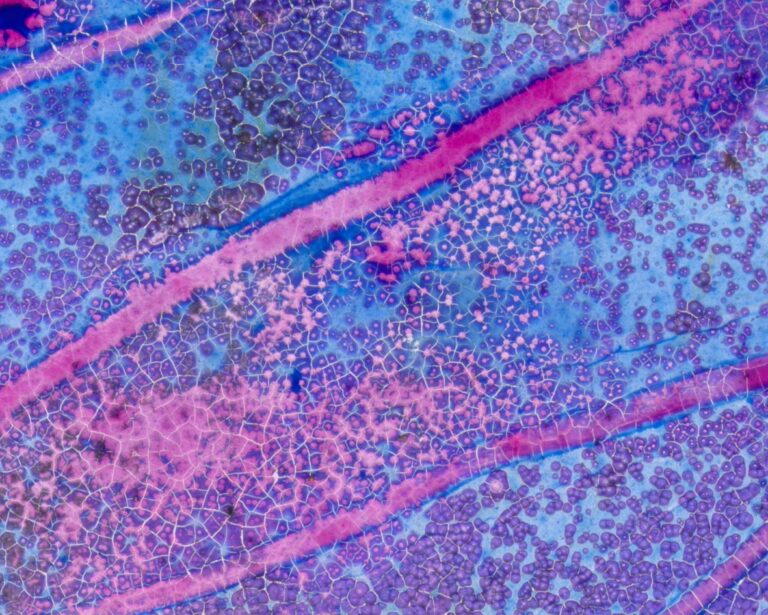

Marynowsky extends this idea further with two new works derived from a project whereby she collected trailers from films with ‘love’ in the title. The first of her ‘love’ works, Adventure, Romance, Heroic, Passion uses a short fragment from the trailer for The Art of Love (1965). Marynowsky corrupts each frame with steel wool and washes of saturated colour. Her interventions amplifies nostalgic value without mawkish sentimentality. The grandiloquent typography used for genre categories like ‘Adventure’ and ‘Romance’ are design clichés in the present, harking back to a time when films were publicised like tabloid headlines. As each word appears on screen as a dated novelty font, Marynowsky declares her fandom in bygone cinema, her investment in looking, her practice as a collector, and her urge to manhandle its contents frame-by-frame.

The companion ‘love’ piece, Falling in Love (Meryl De Niro), uses the trailer from the titular 1984 film. Marynowsky cuts up the celluloid and collages it onto a clear strip of film. The result is an uncanny animation that presents its amorous leading stars Meryl Streep and Robert De Niro as a strange amalgam. The artist’s incisions into each celluloid frame becomes a violent act, converting romance into sabotage. Sergei Eisenstein, the twentieth-century Soviet master filmmaker, believed that montage is a form of conflict – where the juxtaposition of two frames brings about a synthesis of new meaning. Marynowsky evokes Eisenstein’s ‘montage by conflict’ within a single frame composed of multiple cuts.

Heteronormative Hollywood romance detours into gendered action cinema with Bad Boys II Bad Girls. Locating the 35mm trailers for Bad Boys (1995) and Bad Girls (1994), the artist swaps the sound in one for the other. Will Smith appears but Drew Barrymore is heard. Content is inverted but meaning remains the same. The outcome brilliantly underscores the ideological imperatives of dominant cinema and the dangerous game it plays in constructing normative gender ideals.

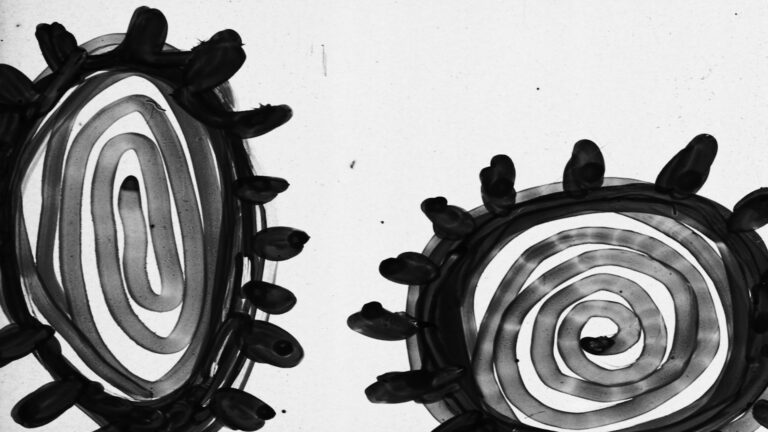

With Motion Pictures Marynowsky creates abstract patterns and forms directly onto a clear strip of celluloid. Unlike her mediated film trailers, these animations dispense with familiar found imagery, but are rich in allusions to pioneers of experimental film animation such as Len Lye or Stan Brakhage.

Tara Marynowsky’s moving images scratch away at ideas embedded in film history, adding washes of colour like an Instagram user who applies filters to echo the past through artifice. Bathing pictures in the nostalgic glow of her own mark-making, the analogue past appears as a critical filter to make sense of an uncertain present tense.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, 2021