Artworks

Installations

While laying on her back Virginia Woolf once remarked “I see the mountains in the sky; the great clouds; and the moon; I have a great and astonishing sense of something there…” Anyone who can recall being a child and obsessively finding faces – or cats claws, or sleeping sling-shots, or amoebic cereal puffs, or mermaid tails – in the undulating cloud clad sky: that person will recall the lucid, unequivocal chaw of recognition. It feels sonic – like an umbilical go-between to our visual pleasure centre. Like reading clouds, the images that surface and sink back into Nathan Hawkes’ drawings function like a sort of Rorschach inkblot- where we, the beguiled, see things. (Or do we?)

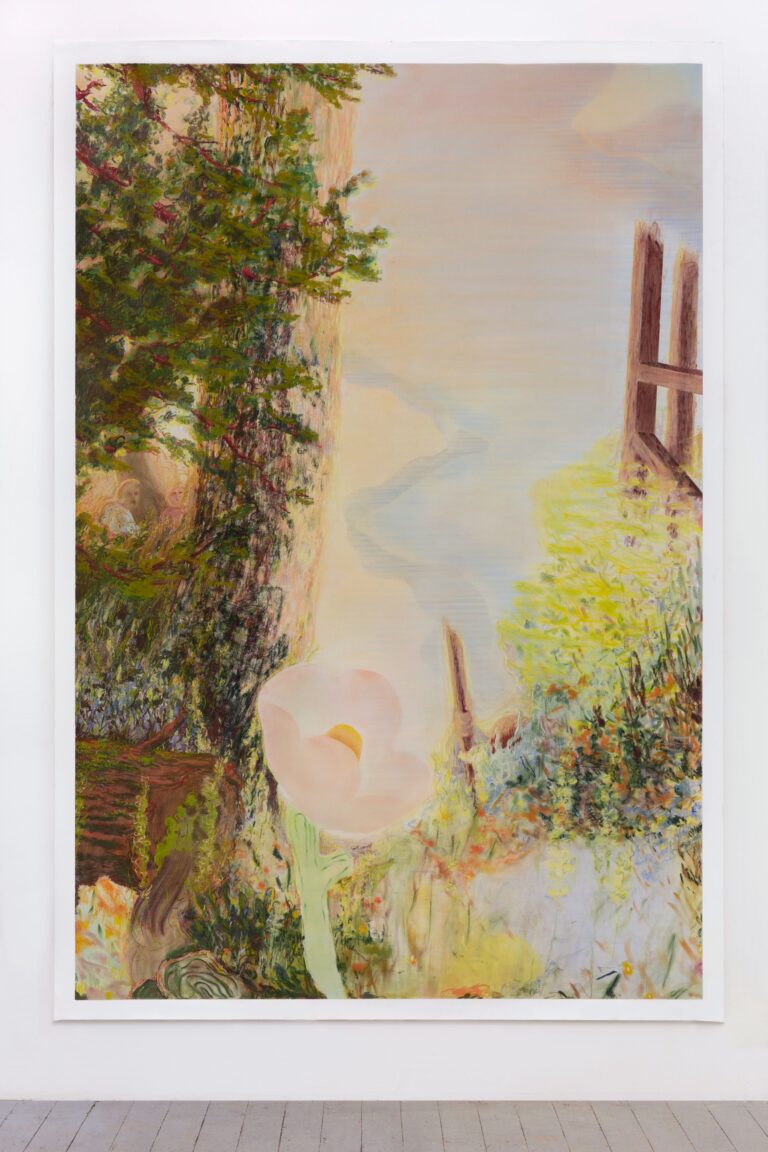

Emotional attunement or mirroring can be defined as the ability to recognise, understand and engage with anothers emotional state. Attunement is also the early term adopted by practitioners of some energy medicines. Energy. Emotional energy. The colouristic summons of Nathans drawings is that of a silent, emotional rave: an ecstatic moment in search of communion with the spiritual world. The flat planes of ‘It is here in a worn-down province’ (2020) finds a luminous figure (if you squint) on the precipice of a space that is devoid of limits, where nature floats like wisps of smoke, cloud-writing itself into the ether. Nonmimetic colour and thick contours with a rhythm of their own, reminding us that meaning isn’t something fixed inside the object of observation, but something that emerges from the attentive encounter with it; a nature of perception. Attunement of attention.

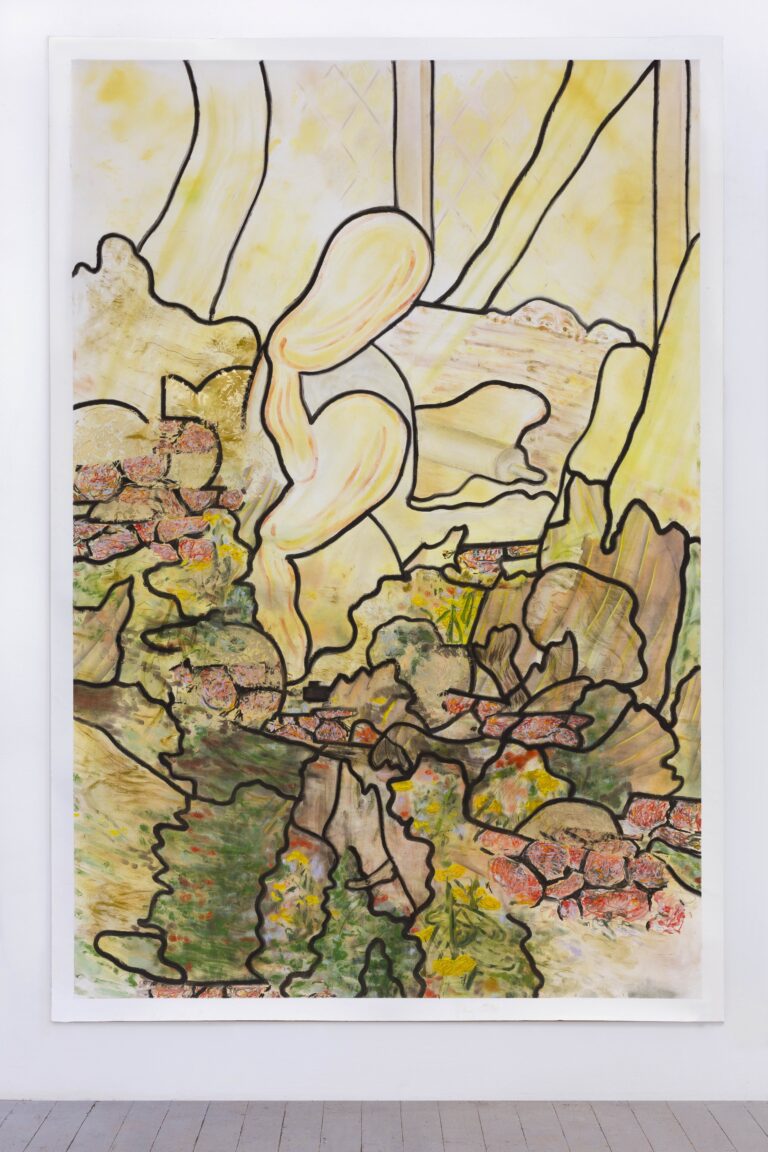

‘cicadas exist, chicory, the cerebellum, cicadas, cobalt bombs exist’ (2020) spins, nothing seems to come to rest (is that two cells in erotic contact?). Flowers, fruits, and rolling pins pop up like bubbles that dissolve into their busy, eddying background, a maze so energetic that it seems to expand laterally.

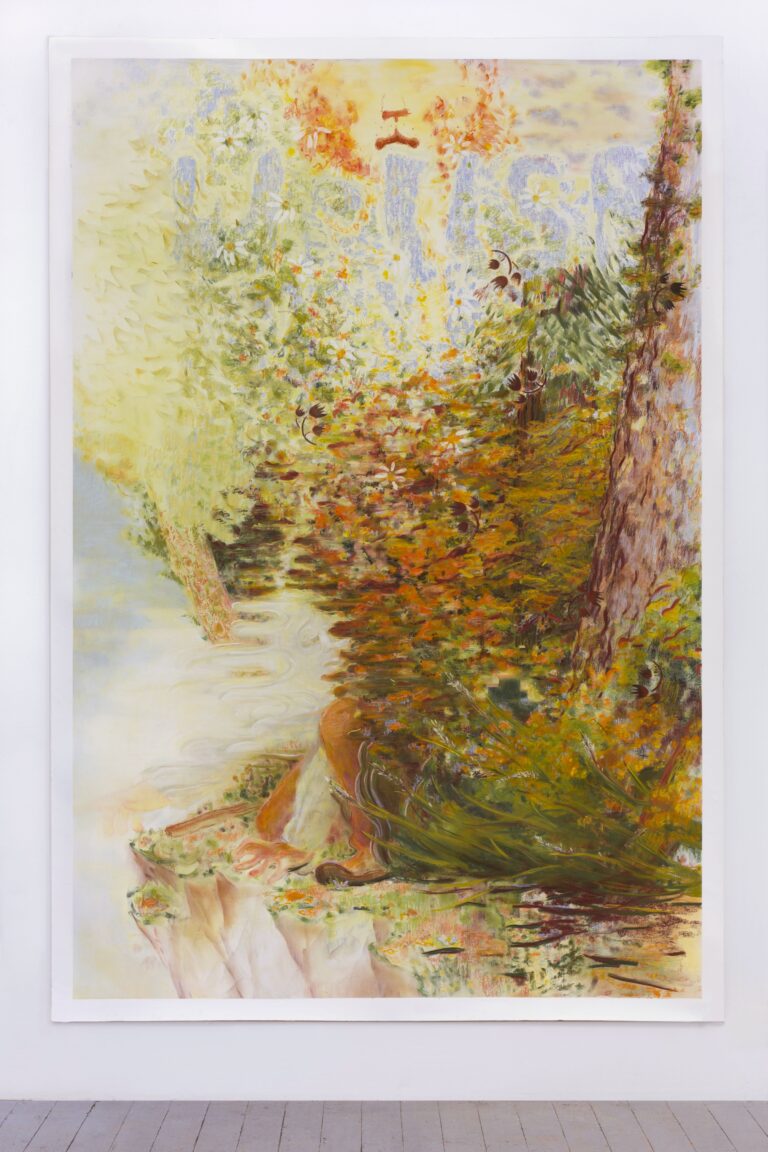

In ‘dreamed summer hour of your childhood’ (2020) line is put to the service of a kind of effulgent atmosphere, a togetherness and separateness with nature (an inter-kingdom

collaboration.) The two faceless ones are entwined with the world – the world in which earthly forces share in the image-making. And the other face, a sentient figure, poised, looking at the looker, prompts the viewer to recall the distinct frisson one gets through deep recognition; is that cloud looking at me?

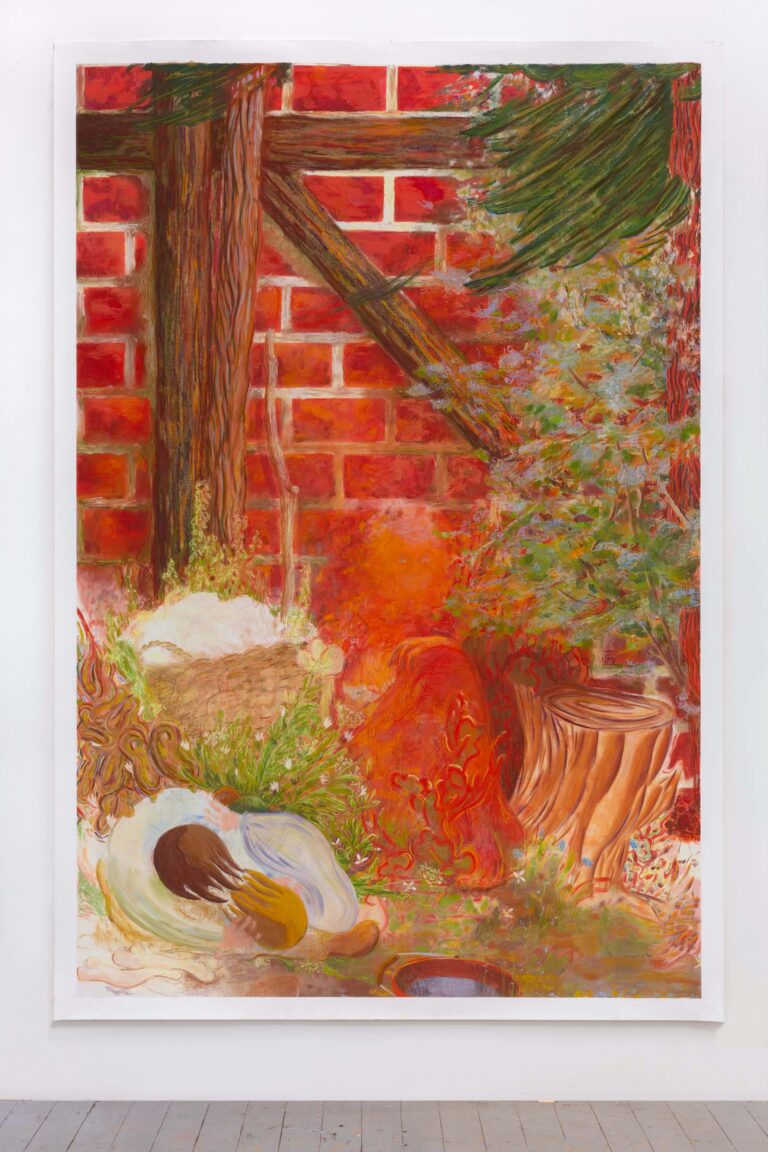

The viewer feels compelled to look at everything at once in ‘they hear the wind tell of the burned off fields/but they are no children/no one carries them anymore’ (2020), but at the same time feels compelled to rely on peripheral vision to do so: to back up, cross the eyes, something is there. Each line seems intuited through the sky like some sort of amathomancy (divination by patterns in dust, dirt, sand, or ashes), where the drawing is talking to itself as it grows, developing the spiky, affectionate self-consciousness native to anything newly energised by growth.

“A bunch of openers!” my grandfather once deemed his keys- as much as it was cute and slightly door-key, it was also a revelatory reminder- keys opened things! In these drawings, I imagine pastels are keys and Nathan’s pictures are doors, framed tenderly by huddled bituminous masses. Through figurative suggestiveness (and some sort of sorcery!), Nathan reminds us that everything is everything -that clouds have faces, that rivers can write – that there is no line between the real and imagined. He reminds us that meaning isn’t something locked inside the object of observation, but something that emerges from an attentive encounter with it. And in this moment, laying on my back, staring up at a clouded sky, I’m reminded of something Helen Frankenthaler once said, “I do very much believe in drawing, especially when it doesn’t show as drawing.”

Emma Finneran, 2020