Justin Balmain

Playground

20 March – 5 April 2008

“Art is pattern informed by sensibility.” Sir Herbert Read, Art Now, 1931

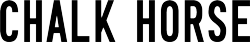

Justin Balmain has created a show that is dazzling, playful and colourful. It is, put simply, an exploration of abstraction, the abstract canon in painting and more traditional ornament. Balmain draws on a wide range of sources — from graffiti tagging to Persian rugs, from wallpaper to children’s butterfly prints. Concurrently on show in Salad Days, an exhibition for Artists in Residence at NAS Gallery (until 29th March), Katie Dyer (curator) writes of Balmain’s work:

The notion that abstraction is pure, autonomous practice is questioned in Balmain’s work, which subtly points to references outside itself whether that be pop culture, art historical precedents or individual experience within larger social constructs.

Reacting to abstract expressionism Balmain’s practice is conceptually driven, mannered and thoughtful; it owes as much to minimalism and conceptual art as it does to the canon of abstraction. Balmain’s work although conceptually aware is also very beautiful and is characterised by its complexity and skill.

In a way the abstract painting tradition began where Balmain has ended up. A painting like Picasso’s Girl in Front of Mirror, or Matisse’s Red Room, owes a lot to the shifting between registers from ornament to abstracted nature. In Red Room, for example, the swirls of the wallpaper are almost exactly replicated in the trees outside the window. The Pop abstractions of Patrick Caulfield and Howard Arkley make similar claims, conflating the aesthetics of middleclass housing with high art. Balmain knowingly crosses social class and aesthetic divides in his work, from the wallpaper tagging, to intricately cut rugs. Balmain’s works seem to double and triple-up on pattern.

Part of the strength of these works is that they use real objects as material. The mass produced items of the everyday are transformed in this exhibition. So instead of an image of wallpaper, already mediated through paint, we get the wallpaper itself. The real is reinstated within the abstract, not a representation of the real but the ornamental object itself. Minimalism, in a counter to Abstract Expressionism would also use machine made objects — bricks, fluorescent tubes, steel panels etc. Balmain similarly could be seen to follow this trajectory. Rugs and wallpapers were considered aesthetic objects, crafted and sometimes totally hand sewn or printed, as in quilts or woodblocked wallpaper; Balmain treats these things perhaps as they are, which is machine made, ubiquitous and cheap (somewhat like an Andre brick). Or perhaps the opposite is true; by presenting them as fine art does the printed wool rug become again something fine and worth looking after.

Ornament is not just a pretty excess or supplement to the real thing. Adolph Loos, who never really thought that ornament was a crime, actually felt that ornament was deeply connected to culture and tradition. In 1924 he wrote, “Classical ornament brings discipline to the formation of utensils, it disciplines us and our shapes.” Balmain’s work shows that our ornamentation from tags to throws, is as important aesthetically as Rothko, and in fact culture needs both.

::

Zoë MacDonell

Shadows on the Floor

20 March – 5 April 2008

“…find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates.” Junichiro Tanizaki In Praise of Shadows (1933)

The story behind this show is summed up in its title. On a residency, alone in her studio, Zoë MacDonell noticed the shadows caste by flowers that she had picked to brighten up the room. Taking out a piece of paper and some chalk she lay down on the floor and traced the shadows that stretched over the paper. This solitary and impulsive act, was a natural and unrehearsed reaction to MacDonell’s immediate surroundings. The final drawing series done over many nights is impressive in its scale and beauty. The repetition of the act marks time as light catches a flower or weed just so. In the day MacDonell would gather flowers, reeds and weeds and in the night, with studio lights on she would draw what had collected.

Each drawing is a little memento of that now lost flower, this trace being all that is left. There is a softness to MacDonell’s approach and a respect for each plant or flower she collected. The tracing is reminiscent of Pliny the Elder’s myth of the birth of painting. A Corinthian maid, Dibutade, drew an outline of her lover’s shadow on the wall before his departure to war. She sat and pined over his image while he was away. The story has been told many times and some say the light source was the sun and some the moon and some say the intimacy of candle light. But three necessities for art, whether that be photography or painting, sculpture or film are in this story: light, an object and a way of fixing an image. Another similar and more contemporary example is the Man Ray Rayograph where images were just placed on photosensitive paper where they left a negative impression in sunlight.

In this way MacDonell’s work goes to the heart of the question “What is painting?” The work is very aware of its process, an act of remembrance, as much as the finished object. The intimacy of the act of drawing, in soft chalks, in the studio, also links to the history of pastel painting whose proponents have been primarily women, such as Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun, or the feminine Chardin. Formally the works are beautiful and this is something MacDonell carefully contrives. The pieces subtly shine in the light, picking up the difference in texture between the white chalk and the white paper. In fact many of the works are studies in white; it is a little known fact that at Parker’s Art Supply there are six different white pastel chalks, all slightly distinct, and all used in these pieces. Otherwise the colours are muted and ghostly and only hint at the vitality of their originals.

The subject of MacDonell’s work can be seen as the imaging of loss. Although there is a desperate attempt to mark out a moment of time, and the trace of a thing, the images show themselves to be inadequate. For Dibutade, motivated by love, the traced line became the basis for fantasies but in the end the complete man was never conjured. MacDonell’s work seems to embody this failure but inbuilt. The very inability to properly represent the objects of her gaze gives MacDonell’s drawings the sublime quality of a spectre.

Zoë MacDonell

Shadows on the Floor

20 March – 5 April 2008

“…find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates.” Junichiro Tanizaki In Praise of Shadows (1933)

The story behind this show is summed up in its title. On a residency, alone in her studio, Zoë MacDonell noticed the shadows caste by flowers that she had picked to brighten up the room. Taking out a piece of paper and some chalk she lay down on the floor and traced the shadows that stretched over the paper. This solitary and impulsive act, was a natural and unrehearsed reaction to MacDonell’s immediate surroundings. The final drawing series done over many nights is impressive in its scale and beauty. The repetition of the act marks time as light catches a flower or weed just so. In the day MacDonell would gather flowers, reeds and weeds and in the night, with studio lights on she would draw what had collected.

Each drawing is a little memento of that now lost flower, this trace being all that is left. There is a softness to MacDonell’s approach and a respect for each plant or flower she collected. The tracing is reminiscent of Pliny the Elder’s myth of the birth of painting. A Corinthian maid, Dibutade, drew an outline of her lover’s shadow on the wall before his departure to war. She sat and pined over his image while he was away. The story has been told many times and some say the light source was the sun and some the moon and some say the intimacy of candle light. But three necessities for art, whether that be photography or painting, sculpture or film are in this story: light, an object and a way of fixing an image. Another similar and more contemporary example is the Man Ray Rayograph where images were just placed on photosensitive paper where they left a negative impression in sunlight.

In this way MacDonell’s work goes to the heart of the question “What is painting?” The work is very aware of its process, an act of remembrance, as much as the finished object. The intimacy of the act of drawing, in soft chalks, in the studio, also links to the history of pastel painting whose proponents have been primarily women, such as Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun, or the feminine Chardin. Formally the works are beautiful and this is something MacDonell carefully contrives. The pieces subtly shine in the light, picking up the difference in texture between the white chalk and the white paper. In fact many of the works are studies in white; it is a little known fact that at Parker’s Art Supply there are six different white pastel chalks, all slightly distinct, and all used in these pieces. Otherwise the colours are muted and ghostly and only hint at the vitality of their originals.

The subject of MacDonell’s work can be seen as the imaging of loss. Although there is a desperate attempt to mark out a moment of time, and the trace of a thing, the images show themselves to be inadequate. For Dibutade, motivated by love, the traced line became the basis for fantasies but in the end the complete man was never conjured. MacDonell’s work seems to embody this failure but inbuilt. The very inability to properly represent the objects of her gaze gives MacDonell’s drawings the sublime quality of a spectre.