Artworks

Installations

“What chance combination of shadow and sound and his own thoughts had created it?”

Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train

Talking Underwater is one of only two figure-based exhibitions in Jasper Knight’s twenty-year career as an artist spanning over fifty shows. The show is an exciting departure for Knight, whose most recent exhibitions Fireworks, Dusk to Dawn and Shade Bakers have focused on soft botanical observations of urban life and whose earlier work often used assemblage to create hard-edged abstractions and figurative renderings reminiscent of industrial landscapes.

This series is based on stills from the 1945 black-and-white noir film The Lost Weekend directed by Billy Wilder. The film focuses on one central character who moves around New York, trapping himself in the city for the weekend. Often Knight’s work centres around one subject matter in each series, whether it be the discarded Renault car factory at Ile Seguin, an island at Boulogne-Billancourt on the western edge of Paris; the dilapidated Docklands of Melbourne; the Junk and the Jumbo Kingdom restaurant that sank within the great Hong Kong harbour; or the artist’s sinking family boat depicted in his exhibition Joan Sea. Talking Underwater however, is the first to follow a single protagonist as opposed to a location or object, acting as a survey of one character in different stages as he descends into the depths of despair.

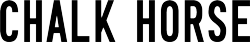

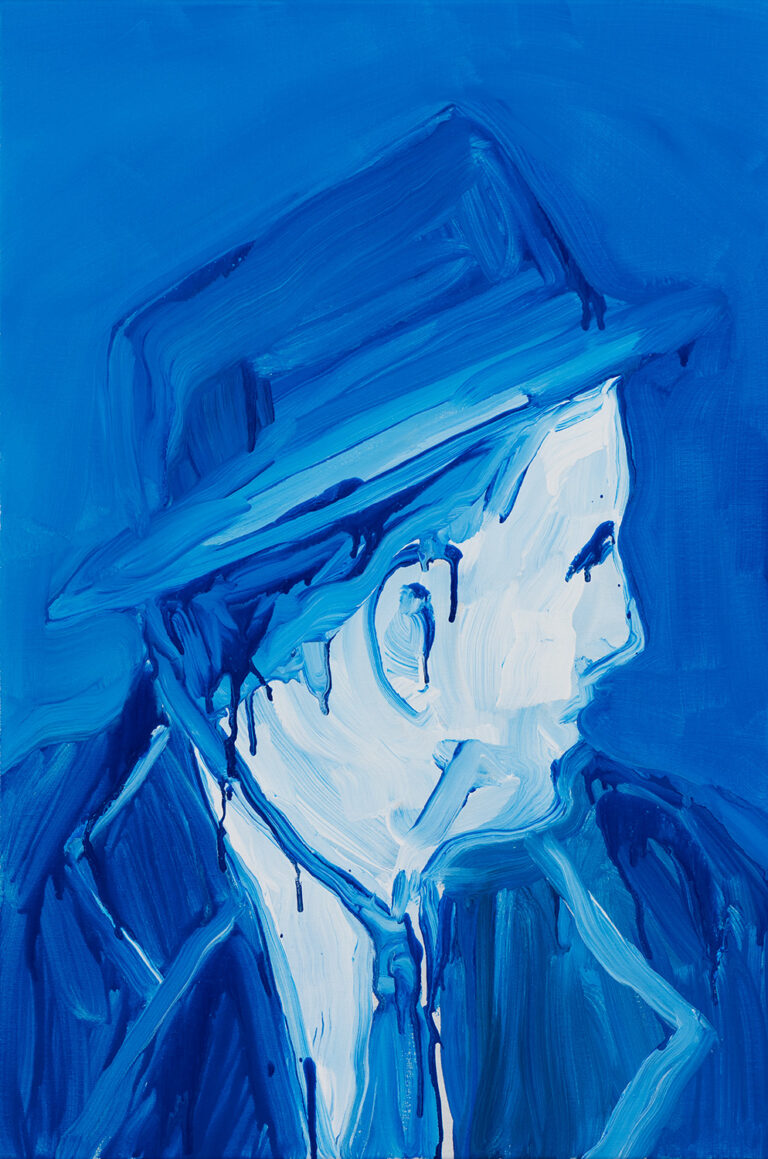

Drawn to the film’s stylistic framework, Knight translates onto canvas the mid-close-up framing and chiaroscuro lighting which narrates the protagonist’s insistent desire for solitude. Knight has always been drawn to early noir films that employ low-key lighting. This powerful technique can convey emotional states through lighting alone, and mark certain story beats by using the highest contrast to intensify shadow. Low-key lighting tends to increase the contrast of the subject against their environment, therefore isolating them. Knight is interested in how this technique, in its drama, creates horror on the face and realism that intensely expresses what the character is experiencing. Unlike Knight’s other work which relies heavily on background to create structure, often melding into the central subject, he uses a minimal palette with loose and expressive brushwork to bring the character forward while pushing the background into the abyss. The paintings therefore use a palette of varying hues of mid-blue, integrating only white as the other colour to create dramatic contrast between light and shadow. Confronting the subject, the paintings impart an artistic impression that is both anonymous and specific, where his protagonist is a persona made estranged to themselves.

In Knight’s earlier works, drips fall mostly off the edges of buildings and urban infrastructure, emphasising form and adding drama to often the throwaway detritus of metropolitan society. Here though, drips envelope and overwhelm the faces of the show, melting away; signifying lost time. While the paintings express the inner world of the man in the film, Knight has dissolved any clear facial features, to create a sense that this could be anyone at any stage of their life. Knight’s interest in urban iconography is long-standing, as someone who has lived in Darlinghurst and worked from a studio on busy William Street in the heart of Kings Cross most of his life. In particular, his works reveal a specific loneliness in a world that moves by. To meet the protagonist in this series then, feels almost strangely similar to encountering the city itself, as another fellow lonely entity. The contracted expressions of Knight’s protagonist gestures towards a distinct, yet intimate and familiar vacancy that seeks refuge in the search of one’s soul and identity. As Don Birnam, the central character of The Lost Weekend, says towards the end of the film, “Walk fast, and don’t turn back.”